I took another peek into the nonsense the Discovery Institute is currently peddling. It’s depressingly shallow, a lot of motivated reasoning and twisted use of the evidence. For instance, Kirk Durston has an article titled Could Atheism Survive the Discovery of Extraterrestrial Life?

, which, as an atheist who would be thrilled to pieces if we discovered alien life of a completely independent origin, seems peculiar.

Here’s his argument, though. The origin of life on Earth is a hard problem (agreed). Current models, as he understands them, suggest that it was an event of exceedingly low probability, so low that it was extremely lucky that it happened here, but it would be extremely unlikely that it would also happen in multiple places in our universe. Therefore, logic dictates the existence of a supernatural creator

. It’s simply, I don’t understand this, therefore god

. It also flops inelegantly into a common creationist theme that there are only two possible models, and if I find a weakness in yours, my model is automatically correct, even if my model has even more flaws, which I conveniently ignore.

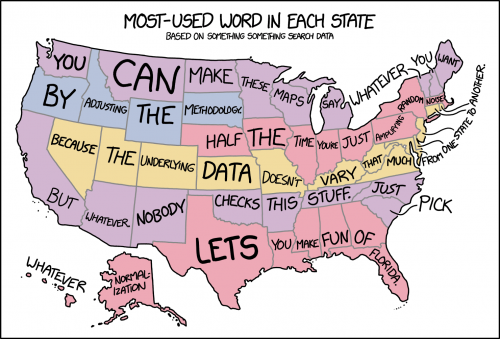

The centerpiece of these kinds of articles is usually some juicy admission from real scientists that we don’t understand every detail of the origin of life, therefore, ha ha, god exists! It’s annoying, because this is how science works, by identifying problems and working to solve them, and creationists love to pervert that methodology into some kind of admission that science is failing and wrong. They never seem to notice, either, that the only way they can steal some credibility is by quoting the scientific literature, or rather, misquoting it.

Durston provides us with a prime example of this tactic.

A 2011 article in Scientific American, “Pssst! Don’t tell the creationists, but scientists don’t have a clue how life began,” summarized our lack of progress in the lab. Of course, there are plenty of scenarios, but creative story-telling should not be confused with doing science, or making scientific discoveries. With regard to “thousands of papers” published each year in the field of evolution, as Austin Hughes wrote, “This vast outpouring of pseudo-Darwinian hype has been genuinely harmful to the credibility of evolutionary biology as a science.”

Evolutionary biologist Eugene Koonin, meanwhile, calculates the probability of a simple replication-translation system, just one key component, to be less than 1 chance in 10^1,018 making it unlikely that life will ever spontaneously self-assemble anywhere in the universe. His proposed solution is a near-infinite number of universes, something we might call a “multiverse of the gaps.”

So three sources: Horgan, Hughes, and Koonin. Is he reporting their work accurately?

He comes closest with his interpretation of Horgan’s article. It is very pessimistic, and is describing the failings of the RNA world hypothesis.

But the “RNA-world” hypothesis remains problematic. RNA and its components are difficult to synthesize under the best of circumstances, in a laboratory, let alone under plausible prebiotic conditions. Once RNA is synthesized, it can make new copies of itself only with a great deal of chemical coaxing from the scientist. Overbye notes that “even if RNA did appear naturally, the odds that it would happen in the right sequence to drive Darwinian evolution seem small.”

This is true. Does anyone believe in a pure, straight RNA world anymore? Not that I know of. The evidence is clear that RNA played a bigger catalytic role in the distant past — we can find vestiges of that role in our cells even now — but the answer is going to be more complicated than just “RNA did it”. And of course, “RNA didn’t do it” doesn’t imply that God did it

.

Unfortunately, Horgan’s alternative is panspermia, which even he doesn’t believe.

Of course, panspermia theories merely push the problem of life’s origin into outer space. If life didn’t begin here, how did it begin out there? Creationists are no doubt thrilled that origin-of-life research has reached such an impasse (see for example the screed “Darwinism Refuted,” which cites my 1991 article), but they shouldn’t be. Their explanations suffer from the same flaw: What created the divine Creator? And at least scientists are making an honest effort to solve life’s mystery instead of blaming it all on God.

I also think he is too pessimistic and doesn’t seem to be aware of the breadth of origin of life research. The recent ideas from Martin and Lane about chemistry and proton gradients have been a breath of fresh air, and reveals the flaw in creationist dismissals of our current understanding — we are constantly learning new things, and what seems like an unsolvable problem now may become a trivial obstacle with further discoveries. It’s one of the virtues of not constraining your search space to the pages of a single old book.

The Hughes article gets a prize for being the most egregiously distorted of the three. For one, it’s not about problems in origin of life studies at all — it’s about poor statistical analyses and over-reliance on adaptive hypotheses. Read the abstract; does this sound like a guy who is questioning evolution?

Sequences of DNA provide documentary evidence of the evolutionary past undreamed of by pioneers such as Darwin and Wallace, but their potential as sources of evolutionary information is still far from being realized. A major hindrance to progress has been confusion regarding the role of positive (Darwinian) selection, i.e., natural selection favoring adaptive mutations. In particular, problems have arisen from the widespread use of certain poorly conceived statistical methods to test for positive selection (1, 2). Thousands of papers are published every year claiming evidence of adaptive evolution on the basis of computational analyses alone, with no evidence whatsoever regarding the phenotypic effects of allegedly adaptive mutations. But it would be a mistake to dismiss Yokoyama et al.’s (3) study, in this issue of PNAS, of the evolution of visual pigments in vertebrates as more of the same. For, unlike all too many recent papers in the field, this study is solidly grounded in biology.

Hughes also does not propose god as an alternative. We’ve got a better option, one that’s actually supported by the evidence.

As well as natural selection, nonselective (or “non-Darwinian”) mechanisms may play a role in the origin of adaptive phenotypes. The most important non-Darwinian process is chance fluctuation in gene frequency or genetic drift, which can lead to the fixation of selectively neutral mutations (those with no effect on fitness) or sometimes even of slightly deleterious mutations. Kimura coined the term “Dykhuizen-Hartl effect” to describe an originally neutral mutation that later becomes adaptive in a changed environment, including a changed biochemical environment resulting from other amino acid replacements in the same protein.

You know how every time I criticize evolutionary psychology for failing to understand that there’s more to evolutionary biology than just selection, I get a swarm of indignant responses that I must be a creationist? This is the same thing. Hughes is properly pointing out that other forces can drive evolutionary change and criticizing the scientists who seem unaware of that, and for that, Durston thinks he’s a creationist ally…or at least, someone whose words can be twisted to pretend he’s an ally.

What about Koonin? This one is interesting, because Koonin is a brilliant thinker and theorist, and always seems willing to take on sacred cows. His book, The Logic of Chance: The Nature and Origin of Biological Evolution, actually does have a chapter on the mathematical probability of the origin of life, and he does use that 10-1,018 number (but not for the origin of a single component: his point is the coevolution of the multiple components of the transcription and translation apparatus is a difficult problem). It is! In the book, Koonin does suggest that a Multiple Worlds hypothesis might offer an out, but I found that as unconvincing as panspermia or worse, the god did it

hypothesis.

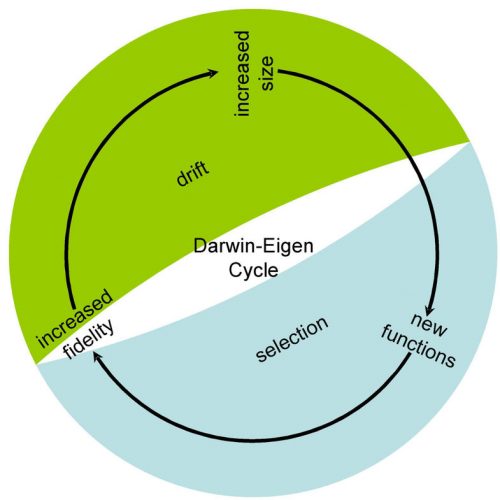

The heart of his argument, though, is the power of the Darwin-Eigen cycle. That is, in a replicating system, there is selection for better fidelity of replication, which allows increases in size and complexity by drift, which is then refined further by selection. The existence of this effect means you can get this constant escalation of complexity and information in cells by the interaction of 3 components, fitness, genome size, and replication fidelity. He’s actually making a powerful argument against another key component of creationist ideology, that you can’t get increases in information without a designer. It’s inherent in the system!

However, he also points out that before the Darwin-Eigen cycle can start chugging along, it needs to cross a threshold. You need some minimal genome size, which you could imagine coming together by chance, but you also need some minimal fidelity — if every generation is randomized, the cycle is not going to be able to get a grip — and that requires functionality that is not likely to arise by pure chance processes. Koonin has no problem as a scientist pointing out that you need a certain threshold of complexity to get the engine of selection and drift going, and recognizes that the emergence of a translation system to convert RNA sequences to protein is a crucial, and difficult breakthrough. That chapter in his book is explaining that this really is a hard problem.

But note that Koonin does not argue that the only alternative is a god — gods make no appearances in the book. Nor does he advocate giving up. Maybe there is a solution, he just hadn’t thought of one in 2011.

So, here’s a paper from 2007, “On the origin of the translation system and the genetic code in the RNA world by means of natural selection, exaptation, and subfunctionalization” which Durston does not cite, which proposes pathways by which the breakthrough could have been made.

The origin of the translation system is, arguably, the central and the hardest problem in the study of the origin of life, and one of the hardest in all evolutionary biology. The problem has a clear catch-22 aspect: high translation fidelity hardly can be achieved without a complex, highly evolved set of RNAs and proteins but an elaborate protein machinery could not evolve without an accurate translation system. The origin of the genetic code and whether it evolved on the basis of a stereochemical correspondence between amino acids and their cognate codons (or anticodons), through selectional optimization of the code vocabulary, as a “frozen accident” or via a combination of all these routes is another wide open problem despite extensive theoretical and experimental studies. Here we combine the results of comparative genomics of translation system components, data on interaction of amino acids with their cognate codons and anticodons, and data on catalytic activities of ribozymes to develop conceptual models for the origins of the translation system and the genetic code.

We describe a stepwise model for the origin of the translation system in the ancient RNA world such that each step confers a distinct advantage onto an ensemble of co-evolving genetic elements. Under this scenario, the primary cause for the emergence of translation was the ability of amino acids and peptides to stimulate reactions catalyzed by ribozymes. Thus, the translation system might have evolved as the result of selection for ribozymes capable of, initially, efficient amino acid binding, and subsequently, synthesis of increasingly versatile peptides. Several aspects of this scenario are amenable to experimental testing.

The authors are Yuri Wolf and Eugene Koonin.

So Durston is incorrect to assume that Koonin gave up with a feeble multiverse of the gaps

hypothesis. That a scientist acknowledges the difficulty of an interesting and complex problem is not a prelude to surrendering and going to church; that’s the creationist solution.

It also produced a very interesting paper.