Since we’ve been talking about the biological basis of intelligence lately, this is appropriate Frans de Waal writes about animal intelligence. His whole point is that this thing we call “intelligence” is multi-dimensional and complex, and that other animals share properties of the brain with us. There are lots of ways an organism can be smart!

But think about it: How likely is it that the immense richness of nature fits on a single dimension? Isn’t it more likely that each animal has its own cognition, adapted to its own senses and natural history? It makes no sense to compare our cognition with one that is distributed over eight independently moving arms, each with its own neural supply, or one that enables a flying organism to catch mobile prey by picking up the echoes of its own shrieks. Clark’s nutcrackers (members of the crow family) recall the location of thousands of seeds that they have hidden half a year before, while I can’t even remember where I parked my car a few hours ago. Anyone who knows animals can come up with a few more cognitive comparisons that are not in our favor. Instead of a ladder, we are facing an enormous plurality of cognitions with many peaks of specialization. Somewhat paradoxically, these peaks have been called “magic wells” because the more scientists learn about them, the deeper the mystery gets.

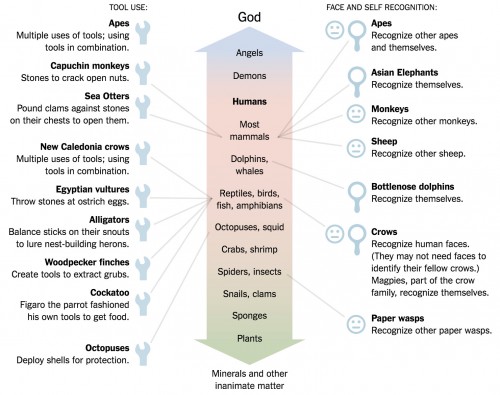

I also very much like this illustration of the scala naturae that shows all the ways intelligence doesn’t fit neatly onto a progressive ladder (the only good use of the ol’ scala anymore is in debunking it).

There isn’t even just one kind of human intelligence! Simon Singh quotes a book Joshua Foer on people with amazing memories, discussing savants. Savants exhibit extreme intellectual abilities, but they’re all different — and they demonstrate that even human intelligence isn’t unitary.

And yet, combing through the literature, one comes across a few rare cases here and there – perhaps less than a hundred in the last century – of savants with remarkable memories who appear to break the rules. What’s most striking about these individuals is that their exceptional memories – “memory without reckoning,” it’s been called – almost always coexist with profound disability. Some are musical prodigies, like Leslie Lemke, who is blind and brain damaged and couldn’t walk until he was fifteen, but can nevertheless play complicated musical pieces on the piano after hearing them just once. Some are artistic prodigies, like Alonzo Clemons, who has an IQ of 40 but can sculpt lifelike animals from memory after just a fleeting glimpse. Some have freakish mechanical skills, like James Henry Pullen, the nineteenth-century “Genius of Earlswood Asylum,” who was deaf and nearly mute, but built stunningly intricate model ships.

This illustrates one of the contradictions inherent in the idea that we can just make people super-smart. They imagine creating a race of neurotypical people who are just more extreme — who are better at engineering and science, for instance. But the whole thing about being neurotypical is that we’re in a state of a kind of balanced mediocrity…all the bits and pieces of our minds are working together in a low-stress fashion, and in a similar way to how most other people’s minds are working. You just can’t make mediocrity extreme.

There certainly are aspects of intelligence that are biological in basis. The blithe confidence that there’s just one kind of intelligence, the mythical g, flies against everything we know about the complexity of brains, human and animal. It’s the myth that allows them to think we can just make people smarter, like turning up a single dial on a big control board. But the truth is that there are hundreds of dials, all working in harmony (we wish), and that everyone is making a different melody. Crank one up, and you fracture the song. You might get something useful to society, but you won’t necessarily make someone who is happily productive.

A couple of decades back, there was talk about different kinds of intelligence – for us humans, I mean. Social intelligence, spatial intelligence, some things like that.

I recall my first computerized test, where it gave harder questions if I got one right. It was the first time I’d felt like I was scoring 50% on a test. In the logic section, it kept giving problems where I had to arrange 6 racehorses in 7 gates, but the brown one didn’t like Hoof-hearted’s jockey. It turns out those are common puzzle-book problems, which are solved with a grid. I didn’t know about the grids, and couldn’t invent them on the fly, so I’d go over time on those questions, and it would then give me a dead-easy question. I’d answer that right, and be rewarded with another damn grid problem.

I stopped on the way home and got a puzzle book, one that told how to make a grid, and by the next day I could have doubled my logical score. But it was too late.

On the math section, the computer couldn’t really present complicated problems, and I took the most logical answer on stuff I didn’t understand, so I wound up with a fairly high score in math. Which was ridiculous. My family seems to have an inherited weakness at math, if we want to consider genetics, here.

I did kick ass in the verbal area, and would happily have waved that test score around. But I didn’t want anyone to see the logic score, nor did I want anyone expecting me to do math.

So yes, we animals all have strengths and weaknesses in various areas, and there are many weaknesses in testing. My dogs have little routines that they figured out, and the two of them are distinctly different. The cats, well, they are cats.

It’s like people who think animals don’t have any consciousness–have they never had a pet dog or cat? Anyone who’s had more than two dogs or cats (or other pets, I expect, but dogs and cats are most common in the USA) can see they have different personalities and different skills.

Apparently “pay attention to what’s going on around you” is one of the rarer forms of human intelligence.

That’s fascinating. I work with animals every day of my life and I’m always surprised how many people don’t seem to understand that animals actually are really smart in certain ways, so it’s very cool to learn about the magic well concept. I’ve heard people try and equate animals with humans, like humans were the gold standard and nothing could be better than being just like a human; not realizing the animal might actually be better at something than a human being. They don’t feel quite so brilliant when they can’t even get that flock of “stupid” sheep through a gate.

Demons don’t put up with that God fella’s crap, so I’d put them above angels.

Tool use: dogs. I have totally seen my dog pick up objects and throw them at my other dog.

The IQ reductionists would argue that “IQ” is itself an aggregate score.

Hsu probably wants to dial up the subscores to produce the maximum

aggregate.

I recall reading Maynard Solomon comment in his biography of Beethoven that

he could not understand how Beethoven, a composer of elaborate musical

structures, was never able to find the product of two numbers no matter how

hard he tried.

Related to Beethoven, one of the reasons his later compositions were so

radically creative was very likely due to his deafness; he was forced to

retreat into his own world.

The way we transcend our limitations is a crucial part of our own creative

development.

There was a nature special about corvids (which are fucking awesome) on PBS that carried out a demonstration that was supposed to compare the intelligence of a trained raven to that of two trained poodles. The animals had to open 3 nested boxes in the right way to get at the piece of meat inside. The poodles had been given practice on each individual box, and IIRC the raven had not.

They determined that the raven was smarter (which I don’t necessarily doubt), because at the time of the trial it opened the boxes quickly and got the food, whereas the dogs just stared at the trainer. My thought was “well, yeah, dogs are trained to be obedient, and their natural history is one of hunting and pack hierarchy. It’s an unfair comparison.”

I wonder where that particular scala is from. I’ve seen other versions, for instance with demons on the bottom below fire, or with snails among the highest invertebrates because slugs-worms-snakes-eels provide the missing links to fish.

There is after all another good use for them, which to see out how people struggled to give order to the incredible diversity of nature. I think some of the attempts might even count as pleasant mistakes, the type you expect when people first trying to classify something, if it didn’t so often come with the ranking of human races up at the top.

That’s unfortunately something people are still trying to force into biology. I recognize the idea of different types of intelligence should be all but self-evident, but I’ve seen it embraced a little too eagerly by the human biodiversity camp: “We’d never say anyone is stupid, but maybe other races just have other types of intelligence! You know, more in-line with nature ones, like animals.” Which for a while gave me a lot of misgivings about the concept in practice.

That’s unfortunately something people are

still trying to force into biology. I

recognize the idea of different types of

intelligence should be all but

self-evident, but I’ve seen it embraced a

little too eagerly by the human

biodiversity camp: “We’d never say anyone

is stupid, but maybe other races just have

other types of intelligence! You know, more

in-line with nature ones, like animals.”

Which for a while gave me a lot of

misgivings about the concept in practice.

That’s the Philippe Rushton argument. In one of his presentations

(available on YouTube) he talks about how Africans score about a 70 on

Raven’s progressive matrices and how a 70 IQ is better suited to people who

were made for menial labor, i.e., made to be slaves for the British gentry.

His language was barely any less blunt (which in a way is to be preferred

to Murray-style caveats and qualifications).

Menyambal@1:

Was that the GRE? Because the same happened to me, except it was one of the verbal section questions. One of the question types I just didn’t “get” (I’ve forgotten which) — so when it came up, I’d invariably flub it, and it would assume I was an idiot and ask me about very simple words for a while, which I’d do well at. I would hope they’re a bit smarter about this test style, but it’s ETS so who knows.

As to your math/logic difficulties: I learned that many schools (including the one that accepted me, for computer science) have decided that only the verbal section of the GRE predicts success in the program — and then only weakly. Turns out that being able to read trumps actually knowing things as you head into 4-6 years of education. Whodathunk. No, wait, that’s bloody obvious.

andrew@5: tool use – cats:

http://i.imgur.com/vdLE8dJ.gif

Reminds me of the debates about whether cats or dogs are ‘smarter’. The argument seems to say more about the humans making it than about cats and dogs.

Frog @ 2

I have seen these people who keep insisting that there is qualitative difference between human conscience and that of animals.

Religion maybe a factor, humans being the only ones with a soul so otherwise they wouldn’t be God’s special little snowflakes.

but what about [POLITICIAN] ?

There is really good evidence for the g factor (i.e. a correlation between people’s ability to do disparate mental tasks) even if the cause for that correlation is still debated.

“Genetics and intelligence differences: five special findings”, Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 98–108; doi:10.1038/mp.2014.105

Using scales or scalar metrics to make comparisons is creeping teleology.

The thing I have to remember when interacting with animals is that they often have a very different experience of the moment than I do. Their senses do not “see” the world in the same way as we do. Most of them do not seem to become as “lost in thought” as we often do but many especially mammals do show the ability to focus their attention on what interests them. I think that difference in interest is one of the primary reasons we think dogs are more intelligent than cats generally cats just do not show very much interest in what we are doing unless it bares closely on their own wants or needs while dogs like to hang out very closely much of the time.

I can’t really imagine what to “see” the world like say a dog but it would probably be so different as likely to be surreal. I am deeply fascinated by intelligence and awareness and how they interact and their expression.

Most of the time people seem to anthropomorphise just about everything any way and if the thing itself does not have those human characteristics the god that causes them does.

uncle frogy

@ gmacs #7

Science News recently reported a similar experiment with wolves and dogs with similar results. It’s good to know that in this rapidly changing world of ours dogs will always be dogs, Clifford Simak notwithstanding.

One definition of intelligence is “the ability to achieve goals despite obstacles.” Since other animals evolved to have different goals than human beings, measuring them on a human scale is an exercise in narcissism. As gmacs pointed out at #7, a dog is going to have different general goal orientations than both a human and a crow.

I think those who wish to “advance human intelligence” need to pay attention to “The Sixth Finger.” Not too much, though — in the story, getting smarter involves developing psychic powers.

As someone with first hand experience of atypical neurology I absolutely agree that human intelligence is about more than just turning a dial.

I have a high IQ and a natural aptitude for logic and spatial tasks, which is presumably one of the goals of ‘increased intelligence’. Unfortunately those atypical qualities come with a near complete absence of social intelligence, which makes achieving anything in a world driven by human interaction functionally impossible.

Of course, those interested in creating minds to specifications would most likely consider variation a flaw, since if you can create people with perfect minds, there is no reason to create anything else. Thus all denizens of the future gengineered utopia will be cognitively identical and no social interaction will be required.

Perhaps he simply didn’t care and was being a stubborn ass about it — not much of a stretch for a guy like him, and putting a lot of trust in 19th century accounts is not a great idea anyway. On the other hand, I’ve known plenty of excellent musicians who are terrible at math and vice versa, which honestly is a little hard to figure out. In any case, yes, even those two forms of applied math aren’t the same kind of “intelligence” (if they’re supposed to be examples of intelligence).

So I guess the moral of the story is that it’s probably useless to talk about someone who is “good at math” or “bad at math” (or music, etc.) because that’s actually an extremely broad and complicated field which requires lots of different skills in different subfields. I suspect that most of the time, people mean that they’re bad at calculating or something like that, which really doesn’t have a whole lot to do with why mathematicians do math or what makes them successful at it.

Well, that makes me a little sad. He was radically creative even when he was writing his earlier stuff. It certainly took a while, years after his death, for his later works to be understood and appreciated, that much is true. And he was forced to rely on his imagination, not a combination of hearing physical sounds and imagining them, true enough; but he had plenty of time throughout his life to build up and exercise that set of muscles, so to speak. (Maybe that’s a more helpful way of explaining it than a “retreat” into a “world.”)

No matter what, whether or not you’ve got some access to physical sounds, composing simply doesn’t happen by passively hearing things: you have to be very much engaged with the material, tossing it around in your head and blending ideas together in all sorts of ways, in order to think about different ways of organizing it. Of course you can still do all of that, without actual noises which are often just a distraction from figuring out what you really want. You’re not trying to be aware of those noises, but trying to be aware of the various features you want some other noises to have. You do need to be able to listen carefully, but at some point, for certain tasks, the literal and superficial “hearing of stuff” that people typically mean by words like “listening” just gets in the way.

Anyway, it shouldn’t be too surprising that those particular “muscles” (types of intelligence) continued to work while some others didn’t work so well. The really bizarre claim is that it’s just one thing, and that’s got to be coming from people who’ve just never stopped to think about it very much (or they know it’s bullshit and they’ve got some other agenda that they want to push).

**** 19th Century Anecdotes.

Perhaps he simply didn’t care and was being

a stubborn ass about it — not much of a

stretch for a guy like him, and putting a

lot of trust in 19th century accounts is

not a great idea anyway.

One would have to have a closer look at Solomon’s sources, but it is not

inconceivable. In music I find that a respect for arithmetic is more

important than arithmetical ability.

**** Absurdity of G.

There’s a video out there of Jeff Loomis, the virtuoso guitarist from

Nevermore, unable to answer a very simple math question; yet what he

improvises on guitar involves a kind of high level computation.

**** Retreating Into His Own World.

As for “retreating into his own world”, Beethoven’s deafness prohibited him

from performing as much as he wanted to. As a result, he had to get the

majority of his musical expression out in composition. That is part of the

“retreat” I referred to. He might have divided his musical life more evenly

between performance and composition otherwise.

Apart from that, for Nietzschean reasons, he was forced to find consolation

in composition (Heiligenstadt Testament).

Menyambal@#1:

I stopped on the way home and got a puzzle book, one that told how to make a grid, and by the next day I could have doubled my logical score.

That’s a great example of one of the big problems with psychological assays – they don’t do a very good job of predicting themselves. If the underlying principle is that there is this thing called “intelligence” and an IQ test measures it, it should fairly consistently place a given subject at the same “intelligence” all the time. If you can do something like learn grids and significantly improve your “intelligence” over night then the test isn’t actually measuring what it purports to – it’s measuring whether you were exposed to grids in school.

There are lots of horrible examples of the flaws in some of these tests. For example some of them would have “missing pieces” – so you were expected to correctly identify that the missing thing in a picture of a tennis court was, of course, the net. Because, you know, anyone “intelligent” knows about tennis. No cultural element there, noooo!

Psychology is another field that could learn a great deal from philosophers. Of course, most of what they’d learn is “U R doing it RONG” For example psychological assays are applied in ignorance of philosophical concepts like “vagueness.” Psychology often attempts to draw lines around things that are vague; they cannot be determined simply by saying “75% of American college-level psych undergrads we paid to do this experiment agree.” That’s a good tell-tale of pop psychology BS – when you see something like Myers-Briggs index (which is a great big wad of pop psychology BS) it asserts that its victims, er, respondents are either “Intruvert” or “Extrovert” based on potentially a single deciding question. IQ tests do the same thing: if you are in the group of people who know how to reason using grids, you are smarter – whatever that is.

The history of IQ testing ought to be such a huge embarrassment for psychologists that they bury it in the cat-box and kick dirt over it. Ditto BMI (which was designed using the methods of pyschologists) and all of Freudian psychology. Actually, the whole field of psychology is such a huge embarrassment for psychologistst that I’m surprised they haven’t renamed it and tried to blame marketing focus groups or something for leading them astray. Unfortunately, that’s backward.

Marcus Ranum @22

That’s just not true. Lots of psychological assays have very good reliability, see this review of tests from a learning center for some examples.

A good book on ethology research into animal cognition is Wild Minds: What Animals Really Think, by Marc Hauser.

Uh, Marc Hauser? Really?

About intelligence: I like this quote from David Owen in “None Of The Above”.

“We don’t know what it is but we’re getting better and better at measuring it.”

I think that this piece also illustrates what’s wrong with many accounts of evolutionary psychology. The examples seem always to go back to ‘our life on the savannah’ when evolution had had a four billion year head start by then and our brains were essentially complete by the time we got there.

Lots of psychological assays have very good reliability, see this review of tests from a learning center for some examples.

Aaah, the first thing on that list is the MMPI.

OK, let’s talk about the MMPI. I had to take that a couple times when I was an undergrad. I’m sad to see it’s even a thing. And it’s a good case in point about reliability: I took it for fun and scored pretty much whatever results I wanted. Well, that means that it’s not measuring what it purports to measure. If it was measuring that I am “hysteric” and I’m not, then all you can say: “it measured that people who answer questions we flag as indicating ‘hysteria’ register as hysteric” If there were actually a condition of “hysteria” and I were actually “hysterical” it should record that regardless of whether I am attempting to lie to it.

The best you can say about it is that it measures pretty accurately whether you gave the answers that put you in a given category. It’s good at that.

Geezus look at the fucking categories it purports to measure! It’s as bullshittic as Myers-Briggs. It even has a Masculine/Feminine stereotypical behaviors column. Let’s see if I can break this down for you: given our idea of what constitute stereotypic behaviors we can test whether someone matches our stereotype. Psychology for the win!

sigaba@16: “Using scales or scalar metrics to make comparisons is creeping teleology.”

I don’t understand what you’re getting at. I would absolutely agree if you had written “creeping ontology”, since (very often, if not always) “scales” tend to reify: “this scale measures; therefore this scale must measure some thing; therefore that thing exists”. But I don’t see why scales lead to attributions of purpose.

Marcus Ranum @23: “when you see something like Myers-Briggs index (which is a great big wad of pop psychology BS)”

However (actually, because it is such a great big wad) it turns out to make a hysterically funny parlor game. I discovered this a couple of months ago at dinner with another mathematician, who had had lunch the day before with a colleague of his (neither a psychologist nor a mathematician) who mentioned the Myers-Briggs BS to him favorably (but off-handedly). My friend asked me if I knew what it was. I said basically what you said, but then, having a smart phone with me, I used a Google search to find one of the many versions of the test for it (I think a 25-question version), which I then proceeded to administer to him.

All right, maybe it’s only hysterically funny to mathematicians and their spouses. But you might try it sometime when you’re well fed, ever so slightly tipsy, and in the company of suitably skeptical old friends.

Marcus Ranum @29, the MMPI-2 and MMPI-A (are designed to detect people altering their responses in an attempt to manipulate the assessment. A quick search on google scholar shows numerous results in both classroom and clinical settings, but I can’t find any full papers available online for free. You’re right that Myers-Briggs is basically meaningless, but many psychometric tests are rooted in empirical data and have proven to be reliable and valid,

I must be a real dodo – I thought g was -9.8 m/sec^2.

Marcus Ranum @29, you’ve correctly identified the weakness of most psychological testing, all surveys/polls, all skill tests, all voting processes, all interviews, and a good bit of diagnostic medicine, among other metrics. They rely on people telling the truth, or in the case of skill tests, trying. They can all be gamed by someone intentionally misrepresenting themselves. One of the fields of study in psychology is how likely people are to lie in various testing situations, which obviously has its practical uses.

There are some alternative psychological test methods that don’t have that weakness. For example, if the test variable is “how prone is Marcus Ranum to hysteria”, the most accurate way of testing this is to place Marcus Ranum in controlled conditions , ramp up the hysteria-inducing stressors, and see how long it takes for hysteria (however that’s defined according to operational definition) to ensue. For best accuracy, Marcus Ranum should be under the impression that the testing variable is something quite different. These methods have yielded good results in the past, but aren’t used much anymore. Budget cuts, obviously.

I fear much of this is missing the point. While lots of animals have something they do better than us, there is certainly good scientific reason to have a rubric to measure how well animals measure up to humans in terms of the tasks humans are good at. You can say whatever you want about the usefulness of studying human intelligence to perform social or eugenic experimentation, but these are not the main; for example it is pretty much the point of a lot of evolutionary studies in early hominids. When you take into account other animals’ tool use, memory, recognition, etc., you can arrive at fascinating generalizations like:

The largest brain-to-body ratio indices (separate orders) are all capable of complex vocalizations (dolphins, apes, birds…). Which I’d call pretty fucking useful since it gives us hints where to look next; now we know language development probably had an awful lot to do with increased brain size, because we weren’t the only ones where it happened. You can thank studies that approached animal intelligence in human-centric terms for this information. They didn’t do it because they are prejudiced against horses, they did it because it will be useful for us!

Point is there is real science at stake here. Statements that attempt to equate the search for those human-like attributes in other animals with random shit animals can do better than we can but which may not even involve the cerebral cortext (the mollusc example above comes to mind), are describing apples and oranges at best and pointless at worst. I’m not sure what it is supposed to be rebutting, or where it is appropriate to make such a comment beyond in that 1990s Scientific American article someone mentioned about “different kinds of human intelligence” – social, spatial, (IIRC physical intelligence was in the article, too). Intelligence studies focused on the development and architecture of the cerebral cortext aren’t interested in “intelligences” based in the cerebellum for a reason.

The other worrisome pitfall of looking at your pet as if there must be something it is “intelligent” at, which I don’t recall anybody suggesting were exactly ‘good-for-nothing’ to begin with, is coming up with signs of intelligence based on anecdotal evidence from untrained researchers who just really like their pets. (No your dog throwing a stick with its mouth is not “tool-use” in any sense of the word). For a better example the OP quote correctly identifies that birds process visual movement faster than humans, hence their seemingly faster reflexes, but so do cats and yet most bird species are clearly on another level compared to all species of cat in terms of memory, problem solving, and other attributes-humans-don’t-suck-at.

At no point in any of this is anyone suggesting you shouldn’t get a pet dog or cat, or that your animal is a dumb animal without its own evolutionary advantages. But there is a reason nobody interested in intelligence is using either of them when birds and apes are available.

*sp* cortex

For a takedown of “g” by a statistician, see this article by Cosma Schalizi at Three-Toed-Sloth:

g_a_statistical_myth. Or, to quote, “About 11,000 words on the triviality of finding that positively correlated variables are all correlated with a linear combination of each other, and why this becomes no more profound when the variables are scores on intelligence tests. ”

Ned

@ taraskan What are you trying to measure? What is your baseline? How (once you have established those first elements) do you know that the tests you use are measuring the thing(s) you wish to measure?

Then there is physiology. If humans had not had the multiple changes in the physiology of the Jaw and its associated musculature would we still be on the savannah grunting? Similarly would our vaunted ability to make and use tools be worth anything if our vision was not binocular?

Would a corvid classify us as unintelligent because we lack the ability to judge how to use 3D airflows and turbulence? Corvids do this for fun; watch crows or jackdaws surfing airflow round cliffs, hedgerows and rooftops. In that vein do the tools we use (e.g. aircraft, radar etc) make us more intelligent and do we suddenly loose that intelligence when the tools are missing?

Intelligence testing measures only the ability to perform certain classes of task that we judge as being related to anthropomorphic intelligence. One thing they do not measure is intelligence as an absolute, because we have no idea of what intelligence is. The words “intelligence testing” and “Intelligence Quotient” are misnomers and anyone who uses them without due qualification is making a gross error.

Sorry – a bit of a hobbyhorse of mine

taraskan:

Your example may point to useful research directions, but it supports PZ’s point, because it’s not about “g.” It says “we’re interested in finding out about vocalization ability, so let’s look for other kinds of animals that share it.” I have no idea if researchers would get a similar result from looking for different species whose members can recognize themselves and trying to find things they have in common. And that in turn is a different question from whether those abilities correlate with some of the other useful things discussed above, including tool use and memory for where things are.