Vestigial organs are relics, reduced in function or even completely losing a function. Finding a novel function, or an expanded secondary function, does not make such organs non-vestigial.

The appendix in humans, for instance, is a vestigial organ, despite all the insistence by creationists and less-informed scientists that finding expanded local elements of the immune system means it isn’t. An organ is vestigial if it is reduced in size or utility compared to homologous organs in other animals, and another piece of evidence is if it exhibits a wide range of variation that suggests that those differences have no selective component. That you can artificially reduce the size of an appendix by literally cutting it out, with no effect on the individual (other than that they survive a potentially acute and dangerous inflammation) tells us that these are vestigial.

I went through this whole ridiculous argument years ago, when the press seized upon an explanation of immune function in the appendix to suggest that a key indicator of evolution was false. It was total nonsense, that only refuted a straw version of evolution. I even cited Darwin himself to demonstrate the ignorance of the concept by the modern press.

An organ, serving for two purposes, may become rudimentary or utterly aborted for one, even the more important purpose, and remain perfectly efficient for the other. Thus in plants, the office of the pistil is to allow the pollen-tubes to reach the ovules within the ovarium. The pistil consists of a stigma supported on a style; but in some Compositae, the male florets, which of course cannot be fecundated, have a rudimentary pistil, for it is not crowned with a stigma; but the style remains well developed and is clothed in the usual manner with hairs, which serve to brush the pollen out of the surrounding and conjoined anthers. Again, an organ may become rudimentary for its proper purpose, and be used for a distinct one: in certain fishes the swimbladder seems to be rudimentary for its proper function of giving buoyancy, but has become converted into a nascent breathing organ or lung. Many similar instances could be given.

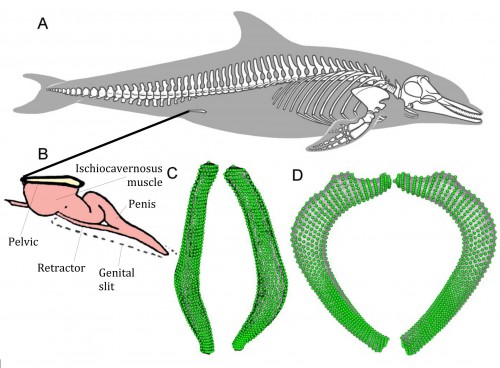

I’m dragging out Darwin because it’s happening again. An analysis of whale pelvic bones supposedly refutes the notion that they are vestigial, because they play a role in sex.

Both whales and dolphins have pelvic (hip) bones, evolutionary remnants from when their ancestors walked on land more than 40 million years ago. Common wisdom has long held that those bones are simply vestigial, slowly withering away like tailbones on humans.

New research from USC and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (NHM) flies directly in the face of that assumption, finding that not only do those pelvic bones serve a purpose — but their size and possibly shape are influenced by the forces of sexual selection.

"Everyone’s always assumed that if you gave whales and dolphins a few more million years of evolution, the pelvic bones would disappear. But it appears that’s not the case," said Matthew Dean, assistant professor at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, and co-corresponding author of a paper on the research that was published online by Evolution on Sept. 3.

Of course the creationists are thrilled to pieces. The press loves the spin of evidence that ‘refutes’ evolution, but the creationists love it even more. After telling us that scientists keep changing the meaning of vestigial, they crow over this rebuke from one of the authors of the study:

This is not just our observation. The scientists who revealed the usefulness of whale hips are rethinking what it means to be vestigial. Or so it sounds from the remarks of biologist Matthew Dean at USC, a co-author of the paper in Evolution, commenting in Science Daily:

"Our research really changes the way we think about the evolution of whale pelvic bones in particular, but more generally about structures we call ‘vestigial.’ As a parallel, we are now learning that our appendix is actually quite important in several immune processes, not a functionally useless structure," Dean said.

Anyone who thinks whale hips are functionless, just like your appendix, should try telling that to a lonely gentleman whale. The career of this evolutionary icon isn’t over yet, I’m sure, but its importance in the evolutionary pantheon is due for a serious downgrade.

I’ve read the paper. It’s about a hypothesis that sexual selection may be maintaining the pelvic bones; it discusses purely evolutionary hypotheses at length, and is not a paper to support intelligent design. Yet here one of the authors is parroting common misconceptions about vestigial organs, and that is infuriating: if you’re going to write papers about a subject, you should know your background adequately. No, finding a retained secondary function for an organ does not mean you have to rethink vestigial organs. See Darwin again.

An organ, serving for two purposes, may become rudimentary or utterly aborted for one, even the more important purpose, and remain perfectly efficient for the other.

It turns out that I also have those same muscles, attached to my pelvis, and I can actually wiggle my penis at will (I hope I don’t have to demonstrate this; any human male will do as a demo, just ask, or try it yourself.) I also use muscles attached to my pelvis to…walk. Whales have reduced, vestigial pelvic bones that have lost the functions needed for walking, but have retained a function for wiggling their penises. This is not a surprise; it is not a revelation that changes our understanding of evolution; I would not get a prize if I showed at the yearly Evolution meeting, dropped trou, and demonstrated my skills with a tassle.

Fools of the Discovery Institute to the contrary, whale pelves are still excellent examples of vestigial organs, and haven’t been ‘downgraded’ at all. And if the IDiots want to argue that we’ve been jiggering the definition to match circumstances, I’ll just point them to that Darwin quote again. Can’t get much more basic and original than that.

An organ, serving for two purposes, may become rudimentary or utterly aborted for one, even the more important purpose, and remain perfectly efficient for the other.

I will say that I wish investigators in evolutionary biology had a better grounding in elementary evolutionary theory, so they would stop inventing these imaginary conflicts to puff up their work.

Let me just add, the paper is fine — it covers the specific topic of its title, Sexual selection targets cetacean pelvic bones, perfectly well. It’s these off-the-cuff remarks to the press that reflect an embarrassing ignorance.

I’m fairly sure that this quotation immediately qualifies this post as my favorite Pharyngula post ever.

Vestigal is also not the same as atavistic. Rare developmental throwbacks.

1. A few humans are born with tails. Like, you know, monkeys.

2. A few whales are born with…legs. Like their land dwelling ancestors.

3. Some people still believe the earth is 6,000 years old, Noah had a boatload full of dinosaurs, and evolution doesn’t happen.

According to his CV, the title of the publication is :

.

I thought that swim bladders were a vestige of lungs, not the other way around. Doesn’t change his point, though.

Whatever good, if any, the human vermiform appendix may do us, prior to the advent of sterile surgery under anaesthesia it killed a whole lot of people, mostly children. I’m pretty sure we’d be better off without it. (Personally I lack not only an appendix but also an ileocecal valve and ascending colon, thanks to some overly excitable surgeons. I don’t seem to miss them.)

I’m baffled by this:

“Everyone’s always assumed that if you gave whales and dolphins a few more million years of evolution, the pelvic bones would disappear.”

Nope, not everyone…

I think it’s also important to remember that boas and pythons have vestigial legs and they do use them. They are not about to evolve them away (because they’ve had a very long fucking time to do so and yet they haven’t and because, again, they do have a use), they are useful, just not for walking.

Blah… making an error when correcting one. Shaaaaame!!

Shouldn’t that be evolution?

(Used preview this time.)

Many creationists have vestigial brains- they still perform their autonomic functions but no longer perform the higher level function of cognition.

I’m looking at the PDF of the article as accepted for publication, and the title is simply “Sexual selection targets cetacean pelvic bones”. Maybe a reviewer talked some sense into the authors and explained that none of this is evidence against them being vestigial.

It also doesn’t use the word “vestigial” in the text, except in the form “vestiges”, as in their concluding paragraph.

Ah, the all important “importantly” — gotta say how important your discovery is! Which explains a lot about the press twist. It’s also telling that in order to make his claim that this “useless” bit is commonplace, he has to cite a 25 year old undergraduate biology textbook.

Isn’t this the kind of thing that should have been caught by the peer reviewers? And corrected before publication?

I heard something about that a while back from one of YouTube’s more flamboyant creationsts: he said that the whale pelvic bones supported the penis during sex. I believe he even claimed that they supported the whale’s (non-existent) penile bone. So, not such a new delusion.

My favorite vestigial organs are wisdom teeth (I think those are vestigial?), which are good for nothing except excruciating pain. (I read some remark, probably apocryphal, that dental pain was the leading cause of suicide in the Middle Ages. Probably apocryphal, but seems plausible!)

So, the creationists are reading research papers! What else is there to do, now that they have proven that the supreme being is not just their feeling but the truth. Now they are out to prove that their brain is not vestigial but that is the way god designed it.

This is my understanding of the current understanding. But in Darwin’s time, I think, it was not understood as such.

GASP! Darwin was wrong! Cue the creationist horde!

Well, tooth abscesses are not an uncommon cause of death in Egyptian mummies of reproductive age….

At some point in our evolutionary past, the appendix may have been a beneficial organ, whether it was for immune reasons or digestion. Then, as our ancestral diets changed and our gut flora changed and the appendix’ size evolved and so forth, there came a time when the risk of death by appendicitis exceeded whatever benefit it might provide. Then, as the environment changed yet again, with the advent of modern surgery with aseptic technique, antibiotics, sanitation, food processing and quality regulation, it became neutral….

Today it might be just a teensy bit in the negative, since it seems to have a propensity for making creationists’ heads explode and there just might, might, be a reproductive penalty for that.

How old does a mummy have to be before it can reproduce?

Indeed, but his original title for the article clearly indicates that his “off-the-cuff remarks to the press” are actually a true reflection of what he believes. Presuming that the journalist who interviewed him did so after the appearance of the article on Evolution, the reviewer who convinced the authors to change the title clearly did not get through to him why it was so wrong.

I’m still waiting for the Discovery Institute to explain why God gave men nipples.

Well, we have to remember that scientists and humans, and the process of science is subject to the vagaries of humans as social organisms. The need to win funding means an impetus to make a work standout, and an easy way to do that is to present it as if it conflicts with or overturns a previously widely accepted assumption.

The scientific method is constructed to, over time, iron out these inconsistencies that arise from the human process, but what we are observing now is the process in situ as it is happening. So of course we are seeing these sorts of inconsistencies pop up, and we are seeing the process of peer review (official and unofficial) starting to work to push it back down.

“I would not get a prize if I showed at the yearly Evolution meeting, dropped trou, and demonstrated my skills with a tassle.”

I dunno. Which prize are you referring to?

So we could have more places for piercings, of course.

I met a creationist who refused to admit what “vestigial” really means…

http://www.skepticfriends.org/forum/topic.asp?TOPIC_ID=13639

I had used as a source of my info this site:

http://talkorigins.org/faqs/comdesc/section2.html#morphological_vestiges

They say, with references that:

Vestigial characters, if functional, perform relatively simple, minor, or inessential functions using structures that were clearly designed for other complex purposes. Though many vestigial organs have no function, complete non-functionality is not a requirement for vestigiality (Crapo 1985; Culver et al. 1995; Darwin 1872, pp. 601-609; Dodson 1960, p. 44; Griffiths 1992; Hall 2003; McCabe 1912, p. 264; Merrell 1962, p. 101; Moody 1962, p. 40; Muller 2002; Naylor 1982; Strickberger 2000; Weismann 1886, pp. 9-10; Wiedersheim 1893, p. 2, p. 200, p. 205).

By definition, a mummy of any age has already reproduced!

The paper also suggests that pelvic bones in female whales are simply carried along for the ride, (pun intended). However the attached muscles in females tighten the vagina during orgasm and may help retain sperm, so they were probably also subject to selection for reasons other then giving Moby Dick an acrobatic penis.

Made two comments on the sb.com version, thought I’d leave them here too:

I think the whole vestigial question vis-a-vis Darwin could be reconsidered in a way that makes Darwin’s point more clear and makes it easier to not mess up an understanding of the modern term “vestigial organ.”

People are confused by the idea of a “vestigial organ” because there are organs that function (for something) that are also called vestigial. The cited case with whales is an example. One might ask if there are organs that do absolutely nothing ever of any kind no matter what vs. those that actually do some things but not the original function and maybe even ask if we should have two terms. But that misses the point, and in fact, most discussions of vestigial I’ve seen miss the larger point Darwin was making.

Lots of organs do not have the function for which they evolved. Consider wings. Darwin notes that the Ostrich wing is “vestigial” (he does not use that word but that is what we would interpret his comments to mean) and “act merely as sails.” But wings on regular birds probably do not serve their original function either. Originally, wings probably acted as something else, possibly sails in a glider, possibly something for cooling before that. The point is, wings for powered flight in birds are vestigial in the Ostrich because they are now used for a different function AND they are reduced in size. Could bird wings in Hawks also be said to be vestigial because they no longer act as cooling mechanisms (assume for a sec that this is true) and are now merely for powered flight? Darwin would not say that because 1) they are not reduced in size and 2) the newer function is major in the bird’s life. We might imagine Ostriches giving rise to a species that does not even have the wings as sails, and still be an Ostrich. We could not imagine a Hawk giving rise to a species that does not have powered flight and still be a Hawk. It would be a tiny Ostrich!

So, there are two things Darwin said about what we now call vestigial organs. 1) They are smaller than their ancestral form and 2) they represent a function having gone away for that species.

The size bit matters in thinking about the history of this idea; Darwin refers again and again to size, about as much as he refers to function. These organs are always described as reduced, and Darwin talks about a general mechanism for organs reducing in part as a response to conservation of materials. Today we would expand that to include more reference to energy (he may have said that somewhere, not sure) and we would talk about loss of gene function. But he does refer to gene function to the extent he could have, in that he talks about an organ becoming vestigial because (proximately) of a change in developmental mechanism.

But step back a bit and really look at what Darwin said. He did not talk about vestigial organs per se; he uses related terms and clearly addresses the concept. But if we were to pay more attention to his words and tried to apply the concept today it is really a bit more interesting and complex.

To Darwin there were three kinds of organs. Regular (not sure what word he would use there), Nascent, and Reduced. A Nascent organ is an organ that will someday be a regular organ. It is a lump or bump or normal organ with a normal function but nothing spectacular, then it evolves to have new and more important function. For example, most (all?) secondary sexual traits would have a nascent form. Consider the regular feathers on the bird’s head and an evolved form that is bigger and has a new function, the brightly colored crest on the bird’s head that now is an element of sexual selection. If you see this process starting, so the bird has enlarged feathers, a small not-quite-crest and it is not of a novel color, you may be looking at a nascent organ. Darwin notes that nascent organs are rare because to identify them we have to see a process that he argues would be dynamic. Nascent organs are literally organs in the process of novel directional selection. Most such organs, by chance, that we happen to see, would be farther along than nascent.

Reduced organs are organs that have reduced selection, or directional selection against (conservation of materials, etc.) with respect to a certain function. PZ’s example is exactly described this way by Darwin in more than one place in the Origin.

Darwin saw the whole thing as a larger process that integrates speciation, diversification, function, and selection. He talked about all of this as evidence for evolution and selection as opposed to the alternative view of divine symmetry in nature (or some other thing having to do with proper expression of the mind of god etc. etc.) Today we focus on the “vestigial organ” as a special unique thing separate and different from all of the other organs. Darwin, rather, described a larger process that, if true, would produce the rarely visible nascent organ, the somewhat more commonly seen reduced organ, and a lot of regular organs, and he put these classes of organs in a dynamic model.

We can refer to Darwin’s concept and keep his excellent idea intact by remembering that dynamic model.

We can modernize the concept by being more tinbergian about it, and more genetic; all these organs are related to developmental/genetic systems. A set of genes that produces a regular organ (simplifying here) may lose function or effect and that is not selected against, so developmental controlled reduction occurs and there is no selection against that (that accords perfectly with what Darwin said and modern genetics). Ultimately the genetic system only barely does anything, and you have a reduced organ. If the organ becomes totally invisible the genes may still be there; we might call them vestigial genes.

We can clarify the entire discussion of vestigial organs by not calling them that. If we call them what Darwin called them, “Reduced”, and refer to the function as vestigial, things would be more clear.

(Note: Darwin may have used the term “vestigial” somewhere. I did not find it in the later editions of the Origin, looking there because I’m more interested in what he ultimately said than what he originally said. He uses the term “vestige” in his discussion of reduced organs.)

For reference, large parts of Darwin’s discussion of Rudimentary Organs, including reference to Nascent organs, function (or lack of) and process, nicely linking his selection theory to observation s in nature (though I hacked out many of the examples for quasi-brevity):

From Chapter 14, Orign, 6th edition, 1876:

Rudimentary, Atrophied, and Aborted Organs.

Organs or parts in this strange condition, bearing the plain stamp of inutility, are extremely common, or even general, throughout nature. It would be impossible to name one of the higher animals in which some part or other is not in a rudimentary condition. …

Rudimentary organs plainly declare their origin and meaning in various ways. There are beetles belonging to closely allied species, or even to the same identical species, which have either full-sized and perfect wings, or mere rudiments of membrane, which not rarely lie under wing-covers firmly soldered together;…

An organ, serving for two purposes, may become rudimentary or utterly aborted for one, even the more important purpose, and remain perfectly efficient for the other. …

Useful organs, however little they may be developed, unless we have reason to suppose that they were formerly more highly developed, ought not to be considered as rudimentary. They may be in a nascent condition, and in progress towards further development. Rudimentary organs, on the other hand, are either quite useless, such as teeth which never cut through the gums, or almost useless, such as the wings of an ostrich, which serve merely as sails. As organs in this condition would formerly, when still less developed, have been of even less use than at present, they cannot formerly have been produced through variation and natural selection, which acts solely by the preservation of useful modifications. They have been partially retained by the power of inheritance, and relate to a former state of things. It is, however, often difficult to distinguish between rudimentary and nascent organs; for we can judge only by analogy whether a part is capable of further development, in which case alone it deserves to be called nascent. Organs in this condition will always be somewhat rare; for beings thus provided will commonly have been supplanted by their successors with the same organ in a more perfect state, and consequently will have become long ago extinct. The wing of the penguin is of high service, acting as a fin; it may, therefore, represent the nascent state of the wing: not that I believe this to be the case; it is more probably a reduced organ, modified for a new function: the wing of the Apteryx, on the other hand, is quite useless, and is truly rudimentary. Owen considers the simple filamentary limbs of the Lepidosiren as the “beginnings of organs which attain full functional development in higher vertebrates;” but, according to the view lately advocated by Dr. Günther, they are probably remnants, consisting of the persistent axis of a fin, with the lateral rays or branches aborted. …

Rudimentary organs in the individuals of the same species are very liable to vary in the degree of their development and in other respects. In closely allied species, also, the extent to which the same organ has been reduced occasionally differs much. This latter fact is well exemplified in the state of the wings of female moths belonging to the same family. Rudimentary organs may be utterly aborted; and this implies, that in certain animals or plants, parts are entirely absent which analogy would lead us to expect to find in them, and which are occasionally found in monstrous individuals. Thus in most of the Scrophulariaceæ the fifth stamen is utterly aborted; yet we may conclude that a fifth stamen once existed, for a rudiment of it is found in many species of the family, and this rudiment occasionally becomes perfectly developed, as may sometimes be seen in the common snap-dragon. In tracing the homologies of any part in different members of the same class, nothing is more common, or, in order fully to understand the relations of the parts, more useful than the discovery of rudiments. This is well shown in the drawings given by Owen of the leg-bones of the horse, ox, and rhinoceros.

It is an important fact that rudimentary organs, such as teeth in the upper jaws of whales and ruminants, can often be detected in the embryo, but afterwards wholly disappear. It is also, I believe, a universal rule, that a rudimentary part is of greater size in the embryo relatively to the adjoining parts, than in the adult; so that the organ at this early age is less rudimentary, or even cannot be said to be in any degree rudimentary. Hence rudimentary organs in the adult are often said to have retained their embryonic condition.

I have now given the leading facts with respect to rudimentary organs. In reflecting on them, every one must be struck with astonishment; for the same reasoning power which tells us that most parts and organs are exquisitely adapted for certain purposes, tells us with equal plainness that these rudimentary or atrophied organs are imperfect and useless. …

On the view of descent with modification, the origin of rudimentary organs is comparatively simple; and we can understand to a large extent the laws governing their imperfect development. …

It appears probable that disuse has been the main agent in rendering organs rudimentary. It would at first lead by slow steps to the more and more complete reduction of a part, until at last it became rudimentary,—as in the case of the eyes of animals inhabiting dark caverns, and of the wings of birds inhabiting oceanic islands, which have seldom been forced by beasts of prey to take flight, and have ultimately lost the power of flying. Again, an organ, useful under certain conditions, might become injurious under others, as with the wings of beetles living on small and exposed islands; and in this case natural selection will have aided in reducing the organ, until it was rendered harmless and rudimentary.

Any change in structure and function, which can be effected by small stages, is within the power of natural selection; so that an organ rendered, through changed habits of life, useless or injurious for one purpose, might be modified and used for another purpose. An organ might, also, be retained for one alone of its former functions. Organs, originally formed by the aid of natural selection, when rendered useless may well be variable, for their variations can no longer be checked by natural selection. All this agrees well with what we see under nature. Moreover, at whatever period of life either disuse or selection reduces an organ, and this will generally be when the being has come to maturity and has to exert its full powers of action, the principle of inheritance at corresponding ages will tend to reproduce the organ in its reduced state at the same mature age, but will seldom affect it in the embryo. Thus we can understand the greater size of rudimentary organs in the embryo relatively to the adjoining parts, and their lesser relative size in the adult. If, for instance, the digit of an adult animal was used less and less during many generations, owing to some change of habits, or if an organ or gland was less and less functionally exercised, we may infer that it would become reduced in size in the adult descendants of this animal, but would retain nearly its original standard of development in the embryo.

There remains, however, this difficulty. After an organ has ceased being used, and has become in consequence much reduced, how can it be still further reduced in size until the merest vestige is left; and how can it be finally quite obliterated? It is scarcely possible that disuse can go on producing any further effect after the organ has once been rendered functionless. Some additional explanation is here requisite which I cannot give. If, for instance, it could be proved that every part of the organisation tends to vary in a greater degree towards diminution than towards augmentation of size, then we should be able to understand how an organ which has become useless would be rendered, independently of the effects of disuse, rudimentary and would at last be wholly suppressed; for the variations towards diminished size would no longer be checked by natural selection. The principle of the economy of growth, explained in a former chapter, by which the materials forming any part, if not useful to the possessor, are saved as far as is possible, will perhaps come into play in rendering a useless part rudimentary. But this principle will almost necessarily be confined to the earlier stages of the process of reduction; for we cannot suppose that a minute papilla, for instance, representing in a male flower the pistil of the female flower, and formed merely of cellular tissue, could be further reduced or absorbed for the sake of economising nutriment.

Finally, as rudimentary organs, by whatever steps they may have been degraded into their present useless condition, are the record of a former state of things, and have been retained solely through the power of inheritance,—we can understand, on the genealogical view of classification, how it is that systematists, in placing organisms in their proper places in the natural system, have often found rudimentary parts as useful as, or even sometimes more useful than, parts of high physiological importance. Rudimentary organs may be compared with the letters in a word, still retained in the spelling, but become useless in the pronunciation, but which serve as a clue for its derivation. On the view of descent with modification, we may conclude that the existence of organs in a rudimentary, imperfect, and useless condition, or quite aborted, far from presenting a strange difficulty, as they assuredly do on the old doctrine of creation, might even have been anticipated in accordance with the views here explained.

Our jaws can be regarded as vestigal traces of gills…that have been repurposed by evolution. A creationist would immediately get this wrong and shout that the presence of jaws disproves evolution.

leftwingfox: “So we could have more places for piercings, of course.”

If you really want freak out the godbots, you should suggest the presence of a few mutant heraphrodites is evolution’s way of trying to create humans that can have twice as fun.

@ Greg Laden

Is a mammalian pronephros and/or mesonephros considered to be a vestigial organ? Neither are functional as excretory organs in mammals (as they form and degenerate during embryogenesis) and yet, to the best of my knowledge, any mutation that perturbs their formation also perturbs metanephros development.

Michel Laurin, Mary Lou Everett & William Parker (2011): The cecal appendix: one more immune component with a function disturbed by post-industrial culture. The Anatomical Record 294: 567–579

Abstract:

“This review assesses the current state of knowledge regarding the cecal appendix, its apparent function, and its evolution. The association of the cecal appendix with substantial amounts of immune tissue has long been taken as an indicator that the appendix may have some immune function. Recently, an improved understanding of the interactions between the normal gut flora and the immune system has led to the identification of the appendix as an apparent safe-house for normal gut bacteria. Further, a variety of observations related to the evolution and morphology of the appendix, including the identification of the structure as a ‘recurrent trait’ in some clades, the presence of appendix-like structures in monotremes and some non-mammalian species, and consistent features of the cecal appendix such as its narrow diameter, provide direct support for an important function of the appendix. This bacterial safe-house, which is likely important in the event of diarrheal illness, is presumably of minimal importance to humans living with abundant nutritional resources, modern medicine and modern hygiene practices that include clean drinking water. Consistent with this idea, epidemiologic studies demonstrate that diarrheal illness is indeed a major source of selection pressure in developing countries but not in developed countries, whereas appendicitis shows the opposite trend, [developed countries] being associated with modern hygiene and medicine. The cecal appendix may thus be viewed as a part of the immune system that, like those immune compartments that cause allergy, is vital to life in a ‘natural’ environment, but which is poorly suited to post-industrialized societies.”

You’re right. Darwin was wrong about this, because when he wrote that the anatomy of obscure subtropical and tropical freshwater fishes wasn’t well known yet – that started around the decade he died. Science Marches On.

The mesonephros only degenerates in females. In males it becomes the epididymis – a rather drastic change in function.

No, of the skeleton that supports the gill slits and associated musculature.

Or rather “[…] [that trend] being associated with modern hygiene and medicine.”

It should be noted that in lots of arguments with creationists, supporters of evolution also often fall into the “vestigial=useless” fallacy, and point out vestigial features being useless as an example of “bad” or “nonsensical” design. (The truth is vestigial features are examples of “bad”/”nonsensical” design for a *different* reason than utility or lack thereof, but explaining that is more complicated that a simple soundbyte to throw out in an argument).

Someone asked about nipples? It’s in there.