But we have to be clear that it is only a hypothesis at this point. I was reading about domestication syndrome (DS) — selecting animals for domestication has a whole collection of secondary traits that come along for the ride, in addition to tameness. We are selecting for animals that tolerate the presence of humans, but in addition, we get these other traits, like floppy ears, patchy coat color, shortened faces, etc.; the best known work in this area is by Belyaev (YouTube documentary to get you up to speed) who selected silver foxes for domesticity, and got friendly foxes who also had all these other differences from their wilder brethren. Similar changes have been seen in rats and mink, so it seems to be a mammalian characteristic that all these differences are somehow linked. Here’s a handy list of the changes in domestication syndrome.

List of traits modified in the “domestication syndrome” in mammals

| Trait | Animal species | Location/source |

|---|---|---|

| Depigmentation (especially white patches, brown regions) | Mouse, rat, guinea pig, rabbit, dog, cat, fox, mink, ferret, pig, reindeer, sheep, goat, cattle, horse, camel, alpaca, and guanaco |

Cranial and trunk |

| Floppy ears | Rabbit, dog, fox, pig, sheep, goat, cattle, and donkey | Cranial |

| Reduced ears | Rat, dog, cat, ferret, camel, alpaca, and guanaco | Cranial |

| Shorter muzzles | Mouse, dog, cat, fox, pig, sheep, goat, and cattle | Cranial |

| Smaller teeth | Mouse, dog, and pig | Cranial |

| Docility | All domesticated species | Cranial |

| Smaller brain or cranial capacity | Rat, guinea pig, gerbil, rabbit, pig, sheep, goat, cattle, yak, llama, camel, horse, donkey, ferret, cat, dog, and mink | Cranial |

| Reproductive cycles (more frequent estrous cycles) | Mouse, rat, gerbil, dog, cat, fox, goat, and guanaco | Cranial and trunk (HPG axis) |

| Neotenous (juvenile) behavior | Mouse, dog, fox, and bonobo | Cranial |

| Curly tails | Dog, fox, and pig | Trunk |

(Hah, reduced brain size. I have a cat, I believe it.)

We have a very good idea of the proximate cause of tameness: the animals have reduced adrenal glands, which means their stress response is reduced, they’re generally less fearful, and they are more open, in early life at least, to socialization. But why can’t genetic mutations that reduce the size of the adrenal gland occur without also changing the floppiness of the ears? There isn’t an obvious physiological link between the two, or other traits in that list.

One idea is that there is a Genetic Regulatory Network (GRN). A GRN is a set of genes that mutually regulate each other’s expression, and may be controlled by the same set of signals. Imagine a lazily wired house in which the lights in the kitchen and the living room are on the same circuit, so you use one switch to turn them both on and off. Or perhaps you’ve cleverly wired in a simple motion sensor, so that when you trip the living room light, the changing shadows concidentally trigger the kitchen light too. Everything is tangled together in interacting patterns of connectivity, so you often get unexpected results from single inputs. The mammalian GRN works, though, so it’s been easier to keep it for a few tens of millions of years, rather than rewiring everything and risking breaking something.

More evidence that there’s a network involved is the fact that these domestication changes can happen incredibly rapidly — Belyaev was getting distinctive behaviors with only decades of selective breeding. What that means is that we’re not dealing with the sudden emergence of mutations of large effect, but with many subtle variations of multiple genes that are being brought together by recombination. This also makes sense. Rather than gross changes that change the entire GRN, what you are doing is tapping into small differences in a number of genes that individually have little or no effect, but together modify the target organ. So in order to change the size of an adrenal gland, you gather together an existing mutation that makes a tiny change in the size while also making ears floppier, and another one that also makes a tiny change in size while also shortening the snout, and another that makes a tiny change while modifying pigment cells.

That’s a very nice general explanation, but in order to advance our understanding we need something a little more specific. What genes? What links all these traits together?

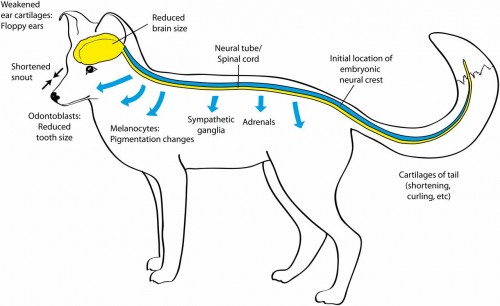

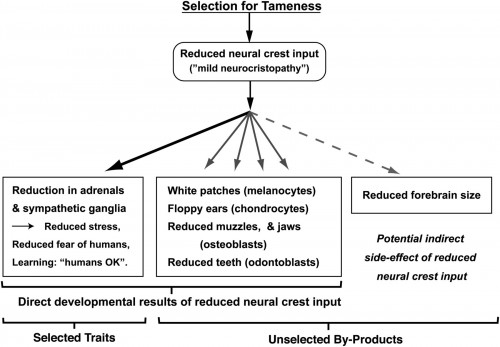

Wilkins and his colleagues have suggested an obvious starting point: it’s all neural crest. Neural crest cells (NCCs) are an early population of migrating cells that infiltrate many tissues in the embryo — they form pigment cells, contribute to craniofacial cartilages, supporting cells for the nervous system, and just generally are found in precisely the places where we see the effects of domestication. So one reasonable hypothesis is that when you’re selecting for domestication, you’re actually selecting for reduced adrenal glands, which is most easily achieved by selecting for retarded or reduced or misdirected NCC migration or increased NCC apoptosis (multiple possible causes!), which has multiple effects.

In a nutshell, we suggest that initial selection for tameness leads to reduction of neural-crest-derived tissues of behavioral relevance, via multiple preexisting genetic variants that affect neural crest cell numbers at the final sites, and that this neural crest hypofunction produces, as an unselected byproduct, the morphological changes in pigmentation, jaws, teeth, ears, etc. exhibited in the DS. The hypothesized neural crest cell deficits in the DS could be produced via three routes: reduced numbers of original NCC formed, lesser migratory capabilities of NCC and consequently lower numbers at the final sites, or decreased proliferation of these cells at those sites. We suspect, however, that migration defects are particularly important. In this view, the characteristic DS phenotypes shown in parts of the body that are relatively distant from the sites of NCC origination, such as the face, limb extremities, tail, and belly midline, reflect lower probabilities of NCC reaching those sites in the requisite numbers. The stochastic, individual-to-individual variability in these pigmentation patterns is consistent with this idea.

They document all the phenotypic changes associated with domestication, and strongly correlate them with neural crest mechanisms. It’s a mostly convincing case … my major reservation is that because NCCs are ubiquitous and contribute to so many tissues, it’s a little bit like pointing at a dog and predicting that its features are a product of cells. It’s a very general hypothesis. But then they also discuss experiments, such as neural crest ablations or genetic neurocristopathies that directly modify the same processes involved in domestication syndrome. So it is a bit helpful to narrow the field from “all cells” to “this unique set of cells”.

I have a similar reservation about their list of genes that are candidates for the GRN — they list a lot of very familiar genes (PAX and SOX families, GDNF, RTKs) that are all broadly influential transcription factors and signaling molecules. Again, it helps to have a list of candidates, it’s a starting point, but in an interacting network, I’d be more interested in a summary of connections between them than in scattered points in the genome.

You need a diagram to summarize this hypothesis, and here it is, featuring the important distinction between selected and unselected traits.

I do have one question that wasn’t discussed in the paper, and would be interesting to answer with better genetic data. We talk about domestication syndrome as if it all goes one way: wild predator becomes more tolerant of humans. But it seems to me that it’s a two-way process of selection, and humans also had to be less stressed out and tolerant of sharing a space with an animal that would like to eat them, or compete with them for resources. Are humans self-domesticated apes? Were we selected for reduced neural crest input? If we figured out the changes in genes involved in domestication, it would be cool to look at dogs and cats and foxes, and then turn the lens around and ask if we experienced similar changes in our evolution.

Wilkins AS, Wrangham, RW and Fitch WT (2014) The “Domestication Syndrome” in Mammals: A Unified Explanation Based on Neural Crest Cell Behavior and Genetics. Genetics 197(3):795-808.

So a lot of the characteristics we consider cute (floppy ears, depigmentation, curly tails) happened accidentally in the process of domestication because of selection for more docile animals? Maybe part of the co-evolution is that we recognize these characteristics as signalling friendlier animals and so the humans that thought those characteristics were cute were more able to interact with the animals, gain the advantages of having animal companions, and survive better? That is, did domesticated animals select us as well?

Another thought: Is the white stripe in the middle of the head/darker colored ears thing significant in any way? Because I keep seeing it as a pattern on dogs at least.

Re: Neotenous behaviour:

Bonobos have been domesticated?

I showed the picture of reduced brain size to my dog. She didn’t understand it.

Would this also help explain “untameable” animals such as the zebra??

@ dianne

Are those features actually universally considered “cute”, though? I don’t think I would have thought of any of them if you’d asked me to describe “cuteness” in animals (I would have probably listed facial traits and expressiveness, and social behaviours like grooming and cuddling).

I look forward with interest to the results of Leslie Fish’s attempts to breed more intelligent cats. I’m fairly sure there is a correlation between stupidity and friendliness to big scary apes, but we don’t have proof that we can’t have smart AND friendly.

There’s a recent book putting forward that hypothesis, but I can’t recall either title or author, and don’t know how well-argued it is. But it is the case that average human brain size has declined significantly over the past 20,000 years.

Is this the Unholy Feline which was once routinely referred to as but a temporary resident?

A couple of thoughts/questions:

The juvenile behavior is also interesting as we have four demon cats and they vocalize differently between humans and themselves. There’s no question they treat each other as peers or competitors, but with me or The Countess their vocalizations get very soft and almost squeaky.

Self-domestication? Are you saying we domesticated ourselves to be better able to live in social groups or self-domesticated in order to better able to to live with our domesticated animals? I could see both or a combination of these two taking place. From my hazy memory of things I’ve read on the subject dogs (or rather some sort of proto-wolf) were the first domesticated animal species. There is evidence they were domesticated during our hunter-gatherer days prior to the invention/adoption of agriculture. It’s also likely that the domestication of dogs occurred not in a single event or conscious attempt at domestication, but by some sort of symbiotic relationship. In this sense one could say that dogs also may have domesticated us.

So what changes should we expect to see in Republicans?

I remember reading once that one result of domestication is that the animal remains in a relatively juvenile state. Behaviorally, this means they are subordinate, which is very handy. Also, it does indeed make them cuter. At least this is true of dogs and cats. Is that still in play? What if anything does it have to do with all this? It does mean a whole suite of differences, all accomplished very quickly since it’s just a matter of not fully maturing, the traits are already there.

So what changes should we expect to see in Republicans?

For all intents and purposes, just like other rats.

soon I will have bred floppy eared cats and we will take over the world!!1!!1!!

however, I will have to rethink my plan if we run into floppy eared cephalopods.

Are there objective tests for ‘tameness’ or is it based on the perceptions of the person or persons responsible for the breeding? If the latter then it would seem that some of the changes may not really be just coming along for the ride but represent unconscious selection biases on the part of the breeder.

@rossthompson

There is the idea that Bonobos have self-domesticated – i.e., their social behaviour selected for less aggressiveness.

I’ve blogged about this, (in German, though)

http://scienceblogs.de/hier-wohnen-drachen/2012/08/28/haben-bonobos-sich-selbst-gezahmt/

The reference is

Brian Hare, Victoria Wobber, Richard Wrangham

The self-domestication hypothesis: evolution of bonobo psychology

is due to selection against aggression

Animal behavior 83 (2012) 573-585

@chris61

The Belayev team had rather strict protocols on how “tameness” was determined, so although it is hard to totally exclude selection biases, it is very unlikely. A good source is

Lyudmila N. Trut

Early Canid Domestication:The Farm-Fox Experiment

American Scientist, Volume 87

(And to continue today’s advertisement, I also blogged about that:

http://scienceblogs.de/hier-wohnen-drachen/2012/08/24/wie-tiere-zu-haustieren-wurden-das-fuchs-experiment/)

Once we learned to cook our food then we no longer needed the strong jaws so it seems reasonable that selecting our mates for cuteness would result in neotenous faces as well as brains. They seem to go together.

Most animals as they develop lose their emotional attachment to their mother but neotenous animals such as dogs do not. Could that explain the so called god-shaped hole in our brains? Could a small child who has a sense of contentment knowing that his parent is nearby keep that feeling into adulthood even though the ‘parent’ only exists in his imagination?

The Count @ 10

Something like this? (Oh geeze, I just forwarded that crap like Weird Al told me not to; that video is 3 years old!)

I have been told that I am barely domesticated, and unfit for civil society. Does this mean that my neural crest input is not reduced?

I’ve been watching The Dog Whisperer with the grandson this summer, and he mentioned that wolves have rounded ears and can’t curl their tails, while domesticated dogs have pointed and often floppy ears and can curl their tails. I have a large German Shepherd. They were bred in 1899 and are still rather close to the wolf in looks. My boy is the size of a wolf, but can curl his tail. Here’s an interesting thing about GSDs. As pups, their ears are soft and floppy. By the time that they are a year old, their ears stand up, but they are quite pointed.

In terms of human “domestication”, can anyone address the theory that humans have had less and less body hair as we have evolved? Could this play into this domestication hypothesis?

Low blow, PZ, low blow!

“Are humans self-domesticated apes? Were we selected for reduced neural crest input? ”

That seems plausible. Early hominims (upright walking apes) had smaller teeth, including smaller canines, and flatter, less prognathous faces. It is proposed that this was a result of selection toward pair bonding to raise young, and selection away from intraspecific aggression and dominance seen in other primates.

I have a hypothesis myself. (CONTENT NOTE: I have no fucking idea what I am talking about.)

Convergent evolution: all of the aforementioned species have domesticated us. Like many orchid species, their genomes would go extinct in the blink of an eye (i.e. a few generations) if humans did not provide adequate shelter, food, care and protection. They are farming us, like ants farm aphids.

(My cat got drunk once and spilled the beans.)

Research like this should serve as a warning to anyone who still thinks breeding humans for things like intelligence is a good idea. You’re likely to get unintended results.

Unfortunately research like this could get used by “scientific” racists as well. “See, it’s just like cats and dogs. The different races have been selected by different breeding goals, so this is why we white people are superior.”

Robb@15

Too late

If domestic cats and dogs are less intelligent, how is it they get us to cater to their every need? Who is smarter now, humans?

It’s a neat hypothesis, but considering there are dog breeds that have prick ears and curly tails (like Huskies) I’m guessing there’s more involved. But as a first approximation for domestication, it’s definitely intriguing.

so if Humans were “domesticated” or self domesticated , or co-domesticated, we’d expect to see in the fossil record individuals with larger teeth, crania, “muzzles” (many of the other traits we wouldn’t expect to be preserved in fossils) – sounds like Neanderthals?

I vaguely remember reading something a number of years ago suggesting that there’s one particular physical characteristic common to domesticated animals and not shared by non-domesticated animals — and that humans share that characteristic. It was something about bone density or structure.

That’s all I remember, and I’m not at all sure it’s valid. Has anyone else heard of this?

PZ has been domesticated. Finally.

(Considers history.)

(Considers current events.)

Are you SURE that we’re selected away from aggression?

Oh, PZ, you silly human! You don’t “have” a cat — you “live with” a cat. And I’d argue that cats were never domesticated; if anything, we domesticated the humans.

robb soon I will have bred floppy eared cats and we will take over the world!!1!!1!!

however, I will have to rethink my plan if we run into floppy eared cephalopods.

.

Ahem. I present to you, the dumbo octopus:

http://tinyurl.com/oj64osy

Oh yes!

Just think of the levels of cooperation, docility, and subservience to authority it requires to wage war and commit genocide….

So we selected individual aggression down from, let’s just arbitrarily say, 10 to 4.

And THEN, with the application of our ginormous brains, with technology and social organization, we INCREASED the amount of actual damage an aggressive individual can do from, say, a 2 to 20000.

And so, the total damage goes from 10×2=20 to 4×20000=80000….

(satisfied smirk, exposes full tum to the fire)

Floppy ears? Reduced muzzle? Curly tails? Tiny little brains? So basically, the pug is the ultimate end result, the Kwisatz Haderach if you will, of selective domestic breeding. Hmmm, yes, this all makes so much sense.

I had always figured that many of these traits were disadvantageous in the wild and thus tended to emerge when the line was protected by an apex predator, and that some traits like curly tails and floppy ears are so associated with domestic animals that they are selected as part of the package of domestic traits. Thus, these traits tend to emerge over and over again.

It would be interesting to note how the study controlled for selection bias.

Look at humans compared to other apes:

Reduced ears

Shorter muzzles

smaller teeth

more frequent estrous

arguably docility

Granted, the ‘smaller cranial capacity’ is a big miss, but I charaterizating us as domesticated primates is pretty on the nose. (A description I first encountered used by Robert Anton Wilson sometime in the seventies).

rossthompson #

They may have self-domesticated to a certain extent, but not nearly as much as we have.

Belyaev also selected for aggression and intolerance of humans in another group of his foxes as part of his experiment. I would like to know what are the physiological side effects of that kind of selection. Are they the opposite of these? The same? Something entirely different?

I thought, generally, dogs have high levels (compared to humans) of linkage disequilibrium–which of course makes breed genotyping relatively easy and suggests that these putative domestication syndrome genes are in LD.

They are also still, iirc, the best single synapomorphy for ‘vertebrates’ (inc. hagfish) or ‘craniates’.

Happens all the time in dogs and pigs.

This is actually awesome. I’d pondered the link myself in the past, specifically after reading about the fox study and wondering if something similar had happened with dogs and other domesticated mammals, though I didn’t even consider adding humans to the list. I look forward to future research :D

Lynna #21:

It means you have a bigger brain!

Don’t you know that the ancestor of all cats was Lucy. They use 100% of their brains to control the 90% of brains that humans don’t use. Size does not matter.

No time to read all comments at present, but given we lack any DS symptoms but the cranial reduction, isn’t it more likely we have only one aspect – naturally selected reduction in adrenal size/aggression coinciding with the increase in size of our social groups?

I read the reverse happens with lemurs – brain size increases in the social species. But our brains are so bloated compared to theirs that we might have the reverse going on at this point – we have all the brain we need for complex human interaction and the only way to improve is increasing efficiency and losing stuff we need less, like adrenaline.

Rulers selecting for docile peasant farmers would seem to be a reasonable thing to expect.

For a different opinion (with lots of documentation) on the violence of society today, see The Better Angels of Our Nature by Steve Pinker. We may well be living in the most peaceful era of our species existence.

docile peasant farmers

When I read Altemeyer, I kept wondering if, maybe, authoritarian followers have been selected for submission/tameability.

I’ve always worried that human observers might judge individuals to be “tamer” if they display the suite of phenotypes (short face, rounded head, floppy ears) that we find “cute”: i.e., the “linkage” is not genetic in the target species but unconsciously built in to there biases of the humans selecting for tameness.

machintelligence @48

Marcus Ranum @ 49

It’s an interesting thought, but difficult to experimentally verify. Untangling the learned behaviours from the biologically-derived ones is going to be tricky. Raising humans devoid of a social context will probably get you on put trial for crimes against humanity.

(Assuming it’s even possible to make that distinction.)

I doubt there’s ever been anything like long term artificial selection in a human population. One could just as easily say members of the ruling class were being artificially bred for conformity, because the maneuvering of other nobility was and the higher middle class would get royalty killed on the semi-regular. Who was calling the shots on all those arranged marriages? Also, no matter how many peasant insurrections were put down through history, they kept coming up, until the French finally made one stick.

Marcus@5 – Zebras aren’t untameable, they’re non-domesticated. The difference is that with non-domesticated animals, you have to start taming each individual from scratch — even if they were born in captivity.