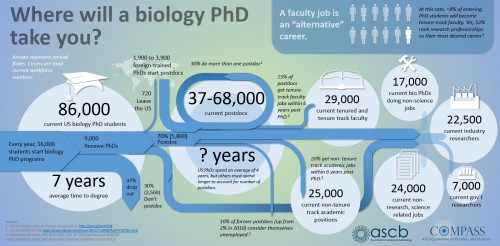

This chart of the distribution of the biology workforce is a bit complicated, but somehow dismaying and reassuring at the same time.

As it points out, over half of all biology grad students hope for that tenure-track research position, but only a small fraction will get it. That’s the depressing part. But at the same time, it shows all the alternative career paths: getting a biology Ph.D. does not doom you to becoming a drunken hobo, and not getting a tenure-track position is not a mark of failure.

It’s also a little misleading. “Current non-tenure track academic positions” ought to be relabeled “Serfdom”.

Graduate school is like a stint in the Peace Corps: several years of penury working your butt off to serve humanity. It may give you some of the best years of your life, but don’t expect it to lead to gainful employment.

To the labs, graduate students are primarily a pool of cheap and disposable skilled labor.

Interesting that there’s no flux arrow between the non-tenure track jobs and tenured/tenure-track jobs, which, if to be taken at face value, would argue that the choice to take a non-tenure-track job as a stepping stone to a tenure-track job (do people do that in bio?) is a risky proposition.

What about the ones who studied evolutionary psychology?

@2: I noticed that as well. It’s hard to believe that “serfdom” is quite as severe a dead end as that would indicate.

Hey at least its marginally better than the life of those of us who decided to go into archaeology. The average undergraduate is consigned to becoming a drunken hobo (i.e., archaeological field technician) or going into graduate school. The average M.A. graduate has the opportunity to get into a professional position in the private industry (called “Cultural Resource Management”) or become a drunken hobo (technician again) and the Ph.D. graduate has the slim opportunity for a tenure-track position, a professional position in the private industry, or become a drunken hobo (adjunct professor or field tech). Unfortunately, most of the jobs are found in the drunken hobo positions. I think the average field tech makes about 1/3 that of the high school educated construction workers they work alongside.

And by “serfdom” you mean “drunken hobo”

I’m actually looking for a PhD position right now, though not in the US. The one thing that stands out for me here is the length of time. The picture says the average is 7 years. I’ve mostly been looking in Europe but there they are talking about an average time to complete the PhD of 3-4 years. Even the longest programme I’ve seen advertised 5 years, but there you started with just a bachelors so it’s like doing a masters along the way. Why is it that US PhD’s seem to take so much longer?

I’m an immunology Ph.D. looking to move into one of those non-science jobs now. Given what I’ve seen in the 10 years since I started my thesis work until now, and what I see with my Biochem Ph.D. girlfriend, I couldn’t possibly recommend Ph.D. research to anyone. The field is essentially a pyramid scheme that rips off grad students for cheap (yet valuable!) labor to prop up an aging cadre of PIs. The career prospects after receiving that Ph.D. are little better than without one, despite 6-7 years of additional work and experience.

When do they ask if people want a tenure track position (the 53% answer)?

I could see that number being a lot higher after 7 days than after 7 years.

And a very large proportion of those tenure-track faculty jobs are not at PhD-granting research universities. While there is nothing wrong with teaching for a living (well, the grading), it’s a very different job than one’s graduate-school mentors have. Very different.

I have a PhD in evolutionary biology, and I am a postdoc right now. I love what I do, but I am sometimes very depressed about the lack of options that I have given my area of expertise and my specialization. Right now, I can only consider staying in academia for ever and learning to life with life-long instability, or leaving for good to do… what? I guess that I will eventually figure it out, but in between… oh, the doubt!

I’m going to have to dig into any supporting information that I can find for this image. I’ve been in the “non-science job” category though I don’t have a PhD, and I have recently been considering going back into jobs related to my degree. Finding out everything I could qualify for would be very useful.

I spent 12 years working in laboratories as an undergraduate and later a graduate student. I ended up having to take a masters degree instead of earning a PhD and going on due to an adult diagnosis of ADHD and Tourette’s Syndrome. My coping mechanisms started failing me at the graduate level and my institution was not very supportive. I tried to find jobs related to my degree (Cell and Molecular Biology), but this was 2009 and the psychological impact of the whole situation is something I’m still dealing with.

Non-scientist parent of a UK biochemistry undergrad here (soon to be a grad). Sometimes people around these parts have really great ideas, so if you’ll forgive my imprudent impudence – any opinions gratefully received: what would you say were wise things to bear in mind and wise directions to look in, for a soon-to-be brand-new biochem graduate in the UK?

@13

Grad school is only worthwhile if you want to enter academia. If you want to pursue research in a non-academic setting, you’ll learn just as much in a lab at GlaxoSmithKline as you would in a lab at Cambridge, you’ll just have better pay and job advancement while learning it.

That’s my perspective as a bitter engineering grad, so take it with a grain of salt, but I doubt biochem is much different.

This cannot be emphasized strongly enough. If you’re not trying to enter academia, there’s a good chance that there’s more good positions that you’ll become “overqualified” for than doors that’ll open by getting a Ph.D.

@14 &15

I disagree. Generally, you can advance a lot further in industry with a PhD than without one. The problem with being overqualified is a true, but it’s typically because you’re applying for an entry level position with a PhD when they can hire someone with a BA for cheap and train them. But a lot of pharmaceutical companies are looking for people with not only a PhD but a post-doc under their belt.

Because they’re simply a different thing. First, the thesis is expected to be bigger, corresponding very roughly to a thesis plus a postdoc over here. Second, PhD students are expected to teach, while over here being a PhD student is usually expected to be a full-time occupation.

And they do take that much longer, it doesn’t just seem that way. In France, doing a PhD has a maximum duration of 3 years; applying for a 4th year is hard, and a colleague who had to do that (because his thesis wasn’t financed, he worked alongside) was flat-out warned “there will not be a fifth year”.

For the last 40 years or so. I have been part of a NSF study of the career paths of doctoral degree recipients in biology, filling out a long questionnaire every two years. An important aspect of my own career path is not, I think, well represented in this graph. I was a research associate in biochemistry for about 10 years, then moved laterally to a research associate position in an entirely different field (environmental science). It was the 1980’s, and I was lucky, in that I had taught myself how to use and program those new “personal computers” (Commodore, IBM) and got a job adapting them to environmental data logging, data management, and immediate-feedback data analysis. Thirty years later I am still doing scientific data management as part of NOAA.

I suppose I would be classified at the far right side of this graph as part of “current government researchers”, but the questionnaire I fill out asks explicitly for information about employment in scientific fields outside that of the doctoral degree. For those in the early part of their careers, it would be good to keep in mind that the doctoral degree doesn’t have to define your field of employment (scientific or otherwise) for the rest of your life. The degree largely indicates that you have demonstrated capability for doing general research: learning what you need to know to get a job done, doing the job, and competently reporting on it. Those are skills useful in other fields, both in and out of science.

Another sense in which this graph may be misleading is that it treats PhD recipients as a steady flowing stream, giving only the current numbers for those at all stages, and ignoring the increases or decreases in numbers over the years. I am not sure, but I wonder if my own cohort, now near the end of their working careers, did not start off smaller than those that followed. I know the study in which I have participated would have data on this, but I am not sure how one would graph that in a meaningful way — perhaps much the same, but with differences in width of those flowing arrows, varying over time, in an animated graph.

I sure wish that this is what I was encountering. I realize that a sample size of one isn’t impressive, but I sure seem to get an awful lot, “oh, you want that higher position? You need experience!” and “want the entry level position? Overqualified!”. Presumably, there’s a sweet spot somewhere, but I’m not finding it. It seems that companies either want someone without a doctorate that they can count on paying relatively low salaries for an extended stretch or someone that already has a decade of industry experience. Maybe that wasn’t the case ten years ago, and maybe it’s not the case in some markets, but I can tell you from experience that it’s a pretty easy decision for me at this point to bail out of science whenever the opportunity become available.

Maybe there’s data that contradicts personal experience, but this seems like an experience that’s fairly broadly shared among myself and friends, who started their Ph.D. program back in ’03 and graduated in ’09 or ’10.

Thank you, timothycourtney, Brandon and gillt. This is not an academic high-flyer, more of a middle-ranking student – not aiming to attempt a PhD but only an MSc. Being a total non-scientist myself, I have only the vaguest idea what sort of work one can try for with an MSc and what areas would be best to look at (most exciting areas they have encountered so far: neuroscience (and a look at animal behaviour), with the sandwich year spent having a great time assisting in a neuroscience lab at a foreign university).

Very grateful for any and all comments, from the above people or from anyone else who would care to!

My field is the red-headed stepchild of biology, wildlife biology. And the hobo thing certainly applies here. Currently, some of my belongings are in the car, and the rest are in my brother’s garage. It’s why I haven’t bothered getting a PhD, I figure it would just overqualify me for most of the available jobs, like the temp tech one that I’m about to start in Utah. Of course, going for a doctorate does put off the interminable job search for a few more years, which is why I suspect so many of my peers are doing it.

So basically 90% of all scientist are drunken hobos.

On the flip side, I’ve encountered a few professors who said they wouldn’t take on a prospective graduate student who didn’t desire to stay in academia.

#18

Very good point and one I think supports the notion that getting a PhD opens doors…generally. That’s my working assumption anyway.

I can’t even find me on this chart – I guess I’m in the 30% that don’t postdoc, but it’s not from lack of trying. I got my phd in genetics in May 2012 and have been looking for a postdoc ever since (internationally), but haven’t had any luck yet. Right now I’m working as an assistant research fellow (basically a tech) doing molecular genetics support for physiologists.

It’s pretty soul destroying, the idea that the fifteen years I put into tertiary education and the passion I have for my field (psychiatric genetics) is all going to end up with me washing glassware and barely earning enough to support my family.

I’m quite lucky (if you can say that) in that my PhD (Virology and Experimental Infectious Pathology) will allow me to do a 2-3 year conversion program to get an MD, which gives me an emergency escape hatch from science if I need it after I do my post-doc. Of course, it also means more loans…

So what you are all saying is that as a biology student that is taking a really fucking long time to finish his degree….i´m royally fucked even if i somehow manage to actually finish it before i´m forced to give up. Brilliant…

Another possible reason for why it takes longer in the States, based solely on what I’ve been told by some of my European colleagues, is because the undergrad is different. In the US, it’s more of a generalist degree; although you do many classes in the major, at least 50% of coursework is general distribution across many academic fields to make one a “well-rounded member of society”. This means that when you get to grad school, you have 2-3 years or so of intense coursework in your specific area, and sometimes people don’t even pick a dissertation topic until near the end of that. (At schools where there are several faculty in one area, students may even rotate between labs for a year or so and only then pick who they want as their advisor.) I’ve been led to believe that in some European countries, you choose your path early and the undergrad is much more specific to one’s chosen area so that there is not so much left to frontload in grad school.

I would chuckle somewhat bitterly at that, but you wouldn’t be able to hear it under the pile of exams and term papers and bylaws revisions and accreditation reports and meeting agendas I’m buried under right now.

@28. Carlie

That is the case in South Africa, or at least the university I went to. People seldom take courses out of their faculty. So every course I took was from the science faculty. First year is general science, so chemistry, biology, physics and maths/stats. After that people pretty much go to a certain department and all their courses are on that subject only. Partly I think it’s forced because to graduate you need a certain number of courses of a certain level but you usually can’t take second or third year courses without the prerequisite courses. So to finish on time there’s not much flexibility.

Jason – that makes sense. In contrast, in most bio programs in the US, in the first two years one takes one bio and one chem each semester as foundation courses, then in the junior year branches out into higher level and elective courses where one might take two bio classes a semester and a couple of more chemistry courses. Three bio classes in one semester might happen once the entire time. The rest of the schedules the four years fill out with physics (one year), math (one to two years), and then all of the other distribution requirements (writing, literature, history, social sciences, language, fine arts, etc.)

@ Brandon

You can increase your sample size to “2”. I’m in my 3rd year of post-doc (biochem) and desperately trying to find something in industry to escape the bench. Whats even worse, I’ve found a few companies have started putting a discreet “PhDs are not eligible to apply” on vacancies for technicians/research assistants, so there goes that option…

@16

This may have been true at one point in time. It isn’t right now. Many pharma jobs are explicitly looking for BS+5 years experience, MS+2 years, or PhD. So your PhD is literally worth 5 years of job experience to them, which you could have gotten elsewhere with better pay and more relevant training.

There are of course other jobs that do require a PhD, but not all of these are entry level (and yes, new PhDs are “entry level” in today’s economy), many require a PhD +10 years experience.

Again, I’m an engineer, so the scales are tilted further to BS than they would be for pure science, but I found significantly fewer opportunities with a PhD than I would have had with a BS. There are fewer people competing with you for jobs, but a lot fewer jobs to compete over.

Oh yes. What makes you a well-rounded member of society and teaches you languages, Latin*, math, writing, literature, history, art, geography, basic chemistry etc. etc. is school as opposed to university (these are a pair of opposites, especially in the German-speaking countries). If you study biology, you’ll have courses like “organic chemistry for biologists” or “introduction to paleontology” in early semesters** – you’re not at all likely to take a course in an unrelated field, and if you take an egyptology exam you likely won’t manage to get any credit for it.

In other words, you Yanks spend the first 2 or so years of university catching up with us, because your school system (as opposed to university system) is in the toilet.

* Only in a few countries anymore; but in Austria, to be allowed to study at a university, you still have to take a Latin exam or to have had Latin in school.

** In Austria years don’t exist at universities. The unit of time is the semester: October to January and March to June. This varies wildly between countries, however.

Doctorates vary a lot between countries. In Austria, you inscribe as a doctoral student – there is no grad school and no application –, then you look for a supervisor and a thesis topic, have them confirmed by the top of the university bureaucracy, and take six semester-week-hours’ worth of courses; there’s a minimum duration of two years and no maximum. In France, you first find a supervisor and a topic, then for financing, and then you apply for grad school; the duration is three years, see above.

Not gonna argue with that.

The interesting thing is that whilst most of the infrastructure in the US is in shambles, the university system is generally still gleaming (perhaps because all of those 1%-er children need to go somewhere?), though this is increasingly changing with the slow but steady defunding of science. I’m lucky enough to be working at a university with massive amounts of private money that could support us for some time if our federal funding took a serious dive. I am also quite lucky in that my field has many non-academic opportunities, although my personal dream would be to do a tenured 50/50 clinical/research split at my current university. However, it is far more likely that I will end up in a CDC, DOD, or industry position.

Also, its most gleaming parts like Harvard and Yale are private (UC Berkeley is the big exception, right?), so even the most Republican Congress can’t defund them as long as their remain enough students whose parents started saving money before the students were born.

Over here, private universities are very rare, and there’s no such thing as a gleaming university; there’s also no such thing as a bad university, which the US seems to have even if we don’t count and its ilk.

Not in schools that rely on public funding. If you’re in a public university that doesn’t have a huge endowment and doesn’t get a lot of private money, you’re shit out of luck because the easiest place for states to cut the budget is in the support they’re supposed to provide to state colleges.

To timothycourtney @32: What kind of entry-level jobs are there for BSc and MSc folks in which to acquire those 5 or 2 years of experience? What are the pay levels?

My daughter is in high school and is interested in majoring in Biology in college. From what I see, I doubt she will like the PhD path (though who knows, she is still young and might mature into it).

Re: international comparisons: In the various European countries, is one expected to obtain a MSc before starting a PhD? One reason PhD programs are so long in the US is because one enters them with a BSc.

For comparison, in Israel one usually takes 3 years to obtain a BA in science, 2-2.5 years for an MSc and around 4-5 years for a PhD. Course work for the BA is in general science and one’s specific discipline, but very little course work outside science. Very few courses are required from PhD students.