So I said

"I wish they didn't bring their agendas into their art…" "Let creators do what they like!" The same people.

— end comment sections (@tauriqmoosa) October 19, 2015

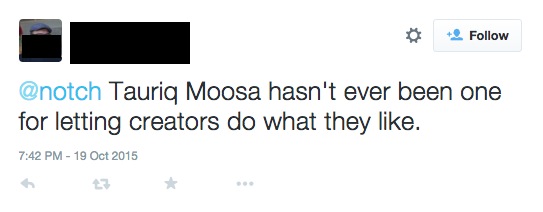

And a hat wearer said in response (to another person who highlighted my Tweet):

This is in reference to my criticism of games in general and, more than likely, Witcher 3 in particular (yes, angry nerds are still angry about that for reasons I fail to understand.)

Look at what this person thinks.

“Letting creators do what they like” – what could this possibly mean? To “let” someone do anything requires an ability to prevent. Even moral conundrums of “letting the fat man die” means being able to prevent his death. When I or other critics write about what games can and should do (and not do), we do so with words and argument; we do not “let” creators do anything because we’re, quite literally, in no position to either allow or prevent them doing so. We’re writing blogposts or articles or Tweets – not laws or business policies that have to be adhered to.

The ideal is that creators – and others – will look at our arguments and agree with them. This won’t happen all the time or even most. But that’s how you start engaging critically: your view sparks another, which sparks another, which sparks another. People engage, debate, think. In the end, they can look at your argument and decide it’s boring, dull, not worth listening to – and move on. It’s an argument, not a legal binding document that, if ignored, will land you in prison.

I want creators persuaded to do better by virtue of them agreeing with my arguments; I want them to go “Hm, that’s a good point: I will include more people of colour!” and then do so, of their own free will, because they read me and others and decided it’s a good idea.

Or not. Or they can totally go “lol no” and decide not to. Either way, they came to their own conclusions because that’s how arguments work.

Even if you disagree with my opinions, to claim I “let” creators I criticise do anything is just obviously false: I do not run any corporations, I do not run boards that censor products – yet it’s a belief repeated so often, I believe such people do believe it. I really think they perceive my disagreement with how media fails to represent people of colour – or whatever – as me preventing creators making their art.

I think GTA V is a hot load of shit, but I’d be incredibly concerned if Rockstar found out they were not allowed to create what they wanted. That’s not just awful for Rockstar but all creators. I don’t want a moral police that Rockstar have to submit petitions to, in order to get a game past. I want Rockstar themselves to engage with criticism and think “hey, maybe homophobia/transphobia/sexism/racism isn’t cool, maybe we shouldn’t?” If they don’t, well, I guess they’ll just keep making their massively successful franchise?

It’s hard to comprehend what power angry people like Hat Person think critics have – but the perception feeds into the worldview that critics “deserve” harassment and righteous opposition. There’s a perception that because critics are being listened to they are also being “obeyed”. The inability to negotiate the difference between criticism and control is a thorn in the leg of fruitful debate, a wrench in cogs of passionate discussions, meaning nothing useful can be produced.

I can guarantee you that most prominent media sites have had famous critics hating Michael Bay’s films – especially Transformers. As far as I know, Mr Bay is still successful and the film franchise was still going strong amidst all the hatred. Being heard doesn’t mean being listened to – let alone obeyed. You can get your argument on the front page of the New York Times and I can choose to ignore it.

“Let creators create what they like!” Well, I can’t. I genuinely can’t do that. Because I can’t do the opposite either. Even if I wanted to, I don’t even know what not letting creators create what they like means – unless you’re talking government censorship.

Critics create criticism – why is our work not allowed? Art is allowed to be criticised; that criticism itself can be criticised. What you can’t do is, instead of disproving arguments, portray them as authoritarian dictates – which is the most bizarre portrayal I’ve seen of contributions from someone who is a freelance writer to a video game website.

The assertion also seems to give immunity to art just because we’re fond of it. Because someone made it and we love it, we don’t want anyone thinking any part of it is bad. It’s sacred and perfect.

But this is nonsense.

You can like and criticise the same thing; it’s possible and important to think about the flaws of the things you love dearly, because nothing is perfect. Criticism is essential to progress: how do we get better if we don’t know what’s wrong? If something is perfect, it means there’s no reason to try. If nothing else, that sounds rather uncreative and boring.

Hate our arguments; ignore me; whatever. But this idea that I or other critics have any significant control over corporations or people with more money and power than us is ridiculous. I dunno: If we had such power, we wouldn’t be freelance writers – we’d just be bringing this stuff out and enjoying it from the comfort of our yachts (those are things that fly right?).

What we’re aiming for is improvement by virtue of persuasion, not dictates; that so many don’t even know what that looks like is kind of alarming to me.

—

If you like my work, please consider leaving me a tip: It’s greatly appreciated.