I got home from London last night after being on a panel with the Rainbow Intersection, a forum for discussions of queer identity, religion and race. The topic was religion and LGBT people – something I’ve already posted about at length – and the other panellists were Jide Macaulay, who runs the Christian House of Rainbow Fellowship; Surat-Shaan Knan of Twilight People, a project for trans and nonbinary believers, and interfaith minister Razia Aziz. I had a blast – all three are top-tier folk, and I’d be thrilled to appear with any of them again.

Jide founded an LGBT church in Nigeria to stop queer believers facing the threats and harassment apostates face – the fact I don’t buy the theology doesn’t mean I’m not glad of that – and works to stop LGBTs being deported today. (He also took my trolling remarkably well.) Surat-Shaan blogs about being trans and a practising Jew for Jewish News – in some ways his background felt like a mirror image of mine, and he speaks at a borderline-absurd number of events. Razia, who made me think I’d been quite cynical, was the surprise: feelgood interfaith rhetoric can cover a multitude of sins, awkward facts obscured in a haze of abstract nouns – mystery-journey-spirit-calling-truth – but there’s a refreshing core of steely realism to her outlook.

Both the Intersection’s organisers, Bisi Alimi and Ade Adeniji, are worth a follow, and Jumoke Fashola, who works in radio and music, was an exceptional moderator. I’m told the discussion was recorded, and that there are plans to release it in audio form – in the mean time, since all the speakers were restricted to a five minute introduction, I’m publishing my uncut opening remarks below.

* * *

‘Is there a place for sexuality in religion?’

I think we can’t stress enough how triggering overt religiosity can be and is to many LGBT people. If I knew an event was taking place in a church, I would avoid it – I don’t feel safe in churches, I don’t feel comfortable in churches. Churches scare me, they make me uncomfortable and they make me [feel] unsafe. In our desire to let [supportive] religious groups play the ‘we’re not all like that’ game, we’re frequently required to pretend they’re mainstream, rather than exceptions, and that so many of us are somehow not legitimately and severely frightened by overt religiosity. That is not an unreasonable or unfair fear, nor one that isn’t based on experience.

These aren’t my words – they’re from a comment left under a post on my blog last December – I’ll come back to it later, because it captures many of my feelings perfectly.

I come to this discussion as a queer person (a bisexual specifically), an atheist, an apostate, an abuse survivor and an ex-Christian, so the question for me is less about sexuality’s place in religion and more about religion’s place in queer communities. I also come to this as a white atheist and a white Englishman – a cisgender man at that – so it’s fair to say I know something about belonging to a populace (several, in fact) with an uncomfortable track record. Equally, as an atheist blogger today, I often find myself at odds with how my community acts.

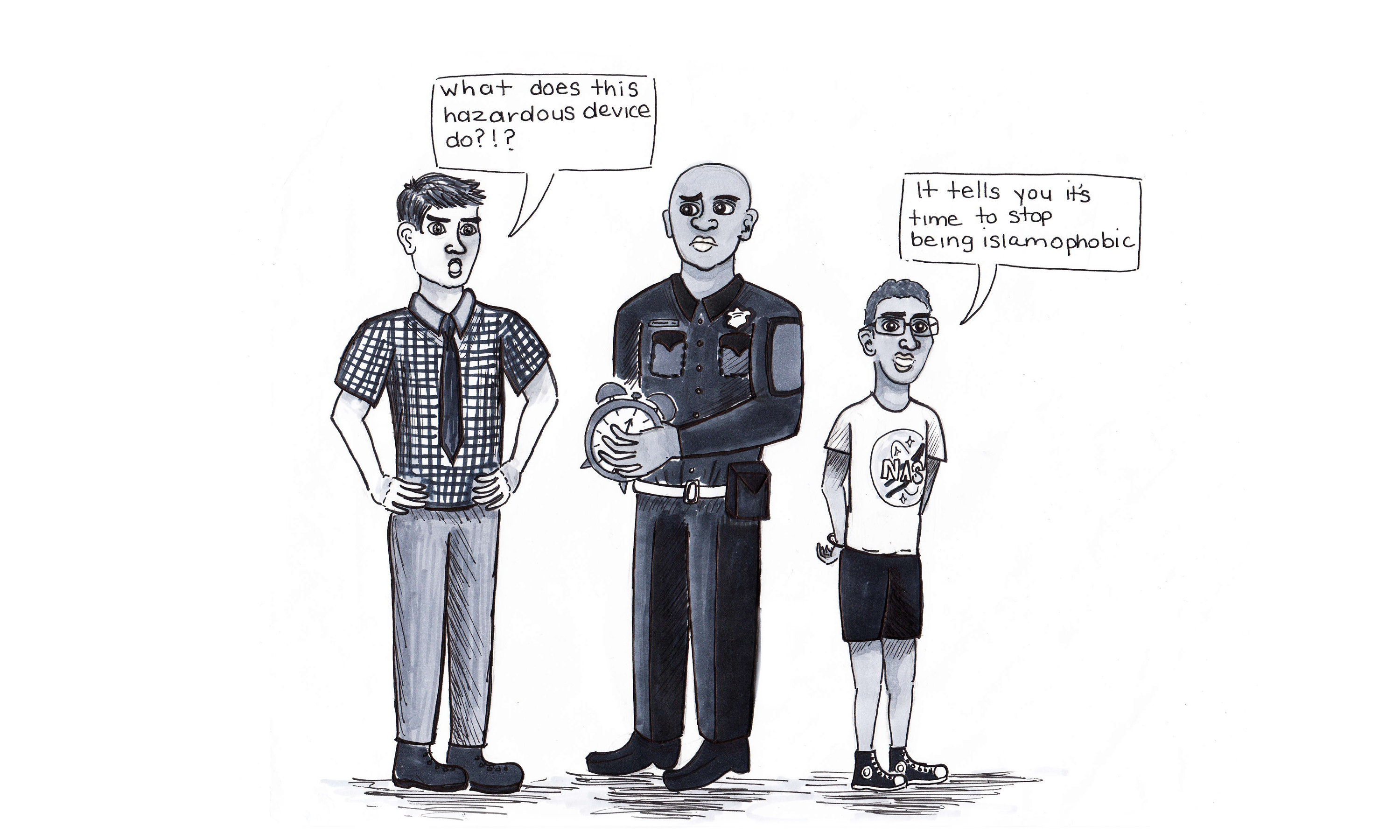

I’m sorry so many atheists harass and dehumanise believers. (The recent Chapel Hill killings in North Carolina were a chilling example.) I’m sorry I often see racism from atheists toward religious communities of colour, both African-American and Muslim, and in particular, that there are atheists trying to pit LGBT people against them. (In the former case, atheists like Dan Savage did this in the wake of Proposition 8; in the case of Islam, I now see atheists joining UKIP and the far-right to do the same.) Most recently, I’m sorry about skeptic groups that promote transphobia and atheists who tell people they’re wrong about their gender BECAUSE SCIENCE.

All that being said, I’ve wondered if the religious panellists here are as willing to own up to their communities’ failings.

I grew up moving between several Christian churches and forms of belief, some fundamentalist, some very much not. You might guess I left religion because I was queer, but that wasn’t the case at all – in my teens, I settled into a gentle, traditionalist but liberal Christianity, and I never felt any internal struggle around not being straight, whether religious or otherwise. At the time, I told myself all the things queer believers tend to say about context, (mis)translation, (mis)interpretation and how Jesus preached acceptance.

But I did suffer religious abuse – vivid, nightmarish threats of hell, claims of demonic possession and countless other things. And I encountered homophobia from other believers that made religious communities feel hostile. And when secular homophobia – which is, in fact, widespread – led me to entrust my faith with my mental health, I ended up trying to kill myself. (I don’t think blaming religion for any of these things is unfair – nor do I think placing the blame on ‘fundamentalism’ is enough. The faith that endangered my life was tolerant, mainstream, entirely non-fundamentalist Christianity.)

In hindsight, I find I cringe more over what I believed as a queer-affirming Christian than over my belief in virgin births and resurrections. It seems such motivated reasoning and contrived circle-squaring, a search less for truth than for something affirming to convince myself I believed, and in the end, wanting to be honest about what I thought instead of lying to myself was part of what led me to leave the church.

However much we ‘queer the text’, finding homoeroticism in scripture and talking about interpretation and context, the fact is that if Jesus existed, the religion he founded has spent most of the last two thousand years marginalising, brutalising, criminalising and killing queer people – by now, on every continent on earth except Antarctica. (Apply and adjust as appropriate for other faiths.) I doubt theres a single queer person here who hasn’t faced queerphobia in Christian or other religious contexts, and some of us have been profoundly harmed by it.

If Jesus meant to preach acceptance of LGBT people, he didn’t do a very good job. A god who can’t get his own message across for most of his followers’ history doesn’t seem plausible to me. Given a global platform and with sincere intent, most children could now tell the world to be nice to queer people without prompting millennia of violence – really, those five words would be enough – and I struggle to believe in a god who lacks the communication skills of a ten-year-old.

Yet I’ve often seen religion promoted in queer spaces. I’ve seen LGBT student groups where clergy came to deliver sermons, where religious flyers were handed out on the door and meetings were moved so as not to clash with church. I’ve seen LGBT discussion events held in churches. I’ve been told to pray and about how God created me. I know I’m not alone in this.

As an atheist and an apostate in the queer community, I feel profoundly uncomfortable with this – not least because LGBT believers often seem set on dismissing realities of religious queerphobia, both historically and today. Many queer people, I think, have sat uncomfortably through public events held to stress the compatibility of queerness and faith sensing precisely this, yet feeling that to voice their ambivalence would be an appalling act of rudeness, bigotry or ‘hate’.

A colleague of mine, Heina Dadabhoy – a bisexual, nonbinary ex-Muslim – wrote this about one such incident:

The worst experience I had was at a local conference about mental health and LGBT issues. Fully half the panels were about religion, and every panel had a representative of what was euphemistically referred to as ‘the faith community’. It is bizarre, to say the last, to sit in a room filled with LGBT folks and hear nothing but praise for religion and disdain for criticism of religion. Any mention of the homophobia in Christianity or any other religion was treated as if it were taboo, or at least unnecessarily hostile.

My guess is that many in this room can relate to that – I know I can.

Unequivocally, I support the work (and existence) of queer religious people like the other panellists here, and of everyone working toward positive religious reform. In many religions, being queer has traditionally meant being viewed as an apostate: in many religions, it’s still regularly assumed that if your sexuality and/or gender is incorrect, you’ve abandoned the faith. Putting an end to that can only be a good thing, because being treated like an apostate is hard: it can mean losing your community or family and having to face social stigma and threats, even violence.

But I know this because many of us, and many LGBT people, really are apostates – whether because of religious queerphobia, religious abuse or other bad experiences, because we can’t believe in a god who has our back or simply because religious beliefs don’t make sense to us. Attempts to be ‘inclusive’ of religious queer people by godding-up our communities with sermons, prayers, clergy and promotion of religious groups often mean excluding us. To that effect, let me share the comment I started with (by a user called Paul) in full.

I think we can’t stress enough how triggering overt religiosity can be and is to many LGBT people. If I knew an event was taking place in a church, I would avoid it – I don’t feel safe in churches, I don’t feel comfortable in churches. Churches scare me, they make me uncomfortable and they make me [feel] unsafe. In our desire to let [supportive] religious groups play the ‘we’re not all like that’ game, we’re frequently required to pretend they’re mainstream, rather than exceptions, and that so many of us are somehow not legitimately and severely frightened by overt religiosity. That is not an unreasonable or unfair fear, nor one that isn’t based on experience, nor one that isn’t based on experience – yet I am expected to treat it as such. No matter how neutral the event is intended [to be], if it is held in church property it is something that will push me out.

And that ‘we’re not all like that’ game is destructive. For me to even remotely consider that a religious ‘ally’ is an ally, I need to know they realise their faith has a bigotry problem – because at the moment our desire to make religious groups comfortable and play PR for them is giving them a pass for bigotry and denying the scale of it in organised religion. How do we counter that if we’re all pretending it doesn’t exist or is ‘fringe’?

So here’s my take-home message: if you’re a secular queer person and you feel uncomfortable around religion, that is absolutely valid. It is not hatred; it is not bigotry. And if you’re a queer believer, that’s just as valid (even if it doesn’t make sense to me) – but please let’s remember there are times when toning down the God-talk is considerate, and please let’s face facts, because atonement starts with contrition.