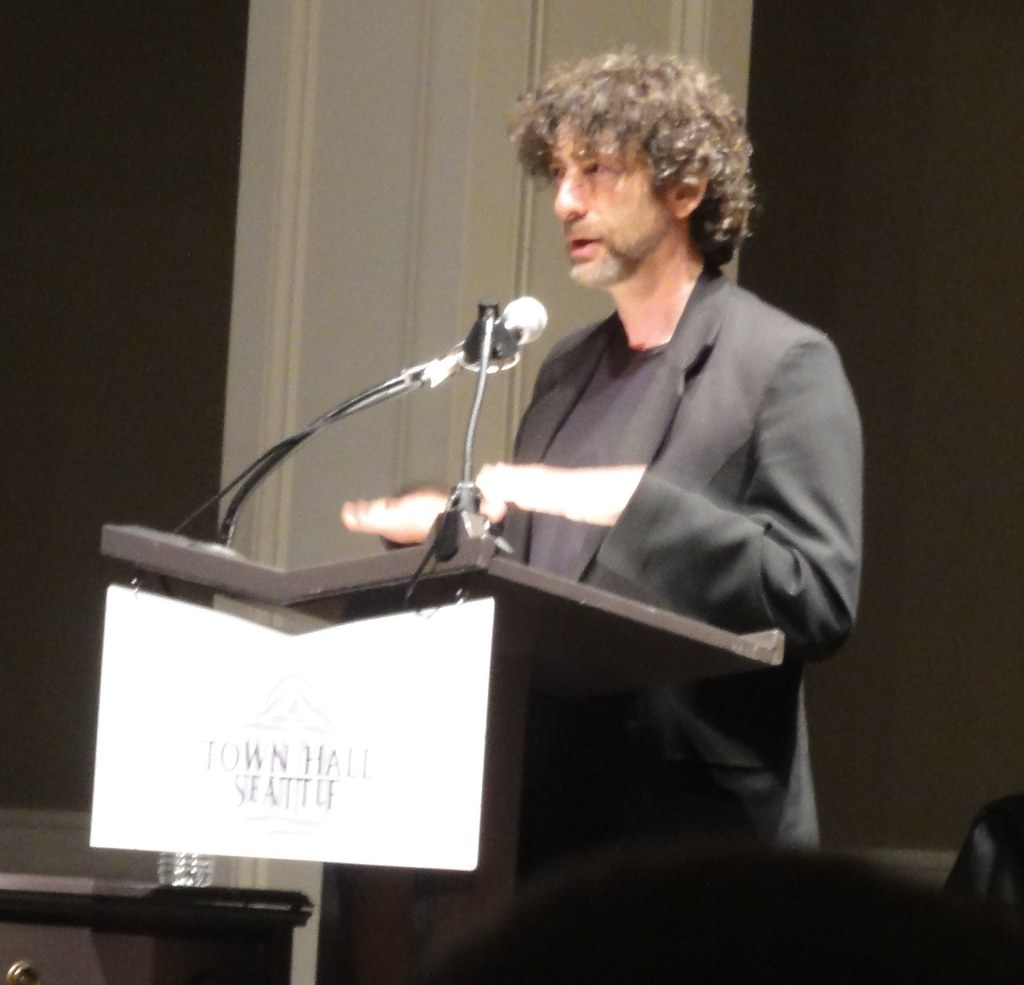

During Neil Gaiman’s appearance at Seattle Town Hall, Neil mentioned a discussion he’d had with Tim Minchin the night before. Tim wanted to know why, since Neil was a rational sort of person, everything he wrote was fantasy.

Neil made a suitably witty reply, which I shall not attempt to transcribe as the audio was teh suck at that point and big portions of it are unintelligible. But it got me to thinking. It’s a good question, actually: why would otherwise rational people write fantasy? Terry Pratchett is a rational man, Douglas Adams was; SF is filled with atheists running around writing about myths and gods and so forth.

Why not write about the real world instead?

I know my gut reaction to Tim’s question was, “Are you kidding? Why wouldn’t he write fantasy? He’s bloody brilliant at it.” I’m sure he’d have been very good writing about really real things and doing very realistic fiction and such like, but no way that could have had the power of Sandman, say, or American Gods. Myth is enormously powerful. And you can use it to say real things that may be a little too real.

I’ve never met Tim Minchin. Possibly never will. But let’s imagine, for a moment, that after I have achieved some modest success and have some SF books out that don’t suck, Tim Minchin and I sit down to dinner under some very odd circumstances, and he asks me that very question. “Dana, you’re a rational woman. You’ve written non-fiction and you’re good at it. Why are you writing fantasy?”

Because I love it. That’s first and foremost: I love speculative fiction. I love science fiction, and I love fantasy, and I love mythic stories, and I love creating worlds. I love my story people and want to do them justice. That’s the first thing.

The second is this: the stories I want to tell are human stories, but they can’t be told here on Earth. That’s just the way it is. I can’t force my characters into an earthly skin; they wouldn’t fit. I don’t want to write stories about the real world. If I’m doing that, I might as well write non-fiction and be done with it. But the real world deeply informs my imaginary worlds, and there’s the turn. There’s the prestige. You see, I’m working a little bit of magic, here.

Because I realized something long ago: people sometimes need imaginary things to help them see what’s real. We’re surrounded by real things all the time and very much want to escape sometimes. I do. When I pick up a novel, I’m not looking for a perfect reflection of the real world. I don’t want to read about ordinary lives. I want a mirror held up, but not just any mirror: it must be one that doesn’t reflect reality faithfully, but twists it around a bit. And I know there are a lot of people like me. They want something fantastic. They want something imaginary and weird and wonderful.

But we only think we’re escaping reality. That’s the turn, you see. The little magician’s trick to make us think we’re getting something we’re actually not. But reality slips in, sometimes very difficult reality. I could go through each and every fantasy novel I own, the ones with staying power, and I could point out to you a place or two or several where very difficult truths got told. I can show you where something I had no interest in became interesting. Things I wouldn’t have touched in a non-fiction book or looked in to on my own because I thought they were too boring, or too grim, or irrelevant, or I simply didn’t know exist. They are things that made me think about very difficult issues, like prejudice, or torture, or morality, or politics. They are things that introduced me to science. I would not be sitting here with you, an atheist with a passion for science, if I hadn’t read fantasy first and started dreaming of other worlds, which in turn led me to explore this one. I didn’t know it was going to do that, but that’s what the very best fantasy does: it changes your perspective. It makes you think, and it makes you wonder, and it makes you explore.

Let’s take my peculiar passion. If I write a book about geology, people who are interested in geology will read it. And there the matter will rest. But if I write a fantasy novel that has got geology in it, people who thought geology was just dull old rocks, people who never would have in a billion trillion years picked up a book about geology, will find themselves reading about geology. They may not realize that. It’s just part of the milieu of that novel, and what they’re reading about is characters in very interesting situations. But they’re getting exposed to geology in the process. And some of them, perhaps a lot of them, will find themselves intrigued enough by the geology bits to go out and explore on their own. Same thing with the biology and the chemistry and the physics I slip in there. Same thing with the other things: myths and legends and religions and atheism. Same thing with the politics and the psychology and the moral dilemmas and – well, I could continue the list, but I think you’re getting the point about now, so I’ll stop.

Because it’s fantasy I’m writing, I can get away with a lot of things that might have sent readers away screaming if they’d been in a more realistic work. That’s the beauty of fantasy: people expect something strange and different in it, so they’re not much fussed when I expose them to strange and different things. Things that would’ve had them howling, “Oh, for fuck’s sake, you’re not going on about that?” if I’d presented it in another format.

We need fantasy. We get very comfortable seeing the world in certain ways, and it all becomes very ordinary. What fantasy does is changes our perspective. We can use it to explore things from a different angle, perhaps an angle we’d never considered before. It invites us to turn things around and upside down and inside out. And when we do that, we may notice things we’d never noticed before. It makes us think in ways we’re not used to thinking. That can lead to all sorts of things. That’s how discoveries are made. That’s how the world is changed.

And that’s the prestige.

Haven’t you heard those terms before? What we fantasy authors are doing is a kind of magic, so let me explain. Actually, let me let someone else do it and save myself the work:

The Pledge: wherein a magician shows you something ordinary, but it probably isn’t. The Turn: where the magician makes the ordinary object do something extraordinary. The Prestige: where you see something shocking you’ve never seen before.That’s really what fantasy is, in the end. That’s what it comes down to. The ordinary, extraordinary. Something shocking you’ve never seen or thought before. All in the form of entertainment, because even those of us realists most passionate about reality like a bit of entertainment now and then.

The real world is phenomenal. It is brilliant and beautiful and endlessly fascinating (as well as awful and terrifying and ugly, let’s not sugarcoat), but sometimes we have to get out of it a while so we can approach it afresh. Fantasy takes us far, far away. We go on a journey, and we see incredible things, and then we come back with our imaginations refreshed. We can see the world with new eyes and new minds. Fantasy can help us gain perspective, one we never would have had without. That’s its power and its glory.

So that’s the speech I’d give. The bugger then might turn around and ask me why I’m not writing pure science fiction, then, but that’s an imaginary question and reply we’ll leave for another day.