When last we left the Skykomish River, it was chillin’ in the basin. You could zip up it in a speedboat, and the rocks were wee little things, most of them no bigger than the size of a fist. Unless you visited at flood stage, you could be forgiven for thinking it’s a tame, sweet thing.

Those rocks should give you pause, however. They’re far-traveled, and they’ve been tumbled and polished and rounded. That’s our first clue the Skykomish isn’t always placid.

Our second clue comes when we head up the highway, past the small towns of Sultan and Gold Bar. The gently rolling basin lands give way to mountains. And these are serious mountains, people, mountains that rise from the earth like they mean it, mountains that don’t shrug off their snow until summer’s well under way. Go just a few miles outside of Gold Bar, and the mountains fold around you, shutting out the rest of the world. There’s a bridge over the Skykomish River, and just beyond it a parking area with river access. Walk down to the river, and you’ll think you’ve come to a different river entirely.

There’s where we are now, between the highway and the railway bridge. A few miles further up the road, the Skykomish splits into its North and South forks, vanishing into the mountains where it’s born.

These are wild waters. You get the first hint when you reach the river from the parking area, and notice you’re having to thread your way through quite a few rather large boulders. Looking downstream, the river vanishes into an aspiring canyon.

|

| Skykomish River, looking downstream |

Look upstream, and you get a sense of just how powerful the river is here. None of these namby-pamby low banks, nossir. No, here, it’s carved out something a bit more respectable:

|

| Skykomish River, looking upstream |

And you notice how it’s plastered its banks with boulders. People go through a lot of effort to pile stuff like this along some of its lower banks in an effort to reduce erosion. Here, the river does its own rip-rap, and does it in style. We’ll see more of that later, and get intimate with them in a forthcoming post. Let’s just say if I had a large yard and a forklift, the banks would be rather a bit less rocky.

Let’s turn our attention to that opposite bank, though. Here’s a panorama of it:

Nice, isn’t that? Look at all those lovely layers! I think an argument can be made that rivers are natural-born geologists. They like to collect pretty rocks, and they sometimes like to cut down through a sequence so that all the nice depositional layers are on display. We shall have a closer look:

Look above the debris fans, and you’ll see some lovely horizontal deposits. Those look like river deposits, don’t they just? And while I can’t swear to it, they might be fine examples of the fining upward sequences Karen talked about when we first went river-walking. I need to read up on rivers before I can speak with any sort of intelligence here, but Karen did us the favor of a short description:

Here’s a phrase you can add to your geologic lexicon (if you haven’t already): “fining upward sequences”. As you pointed out, there’s a flood strong enough to carry cobbles, and then pebbles come down, and the sediment in the exposure fines upward into sand and mud… and then the whole thing repeats. Flows of various geologic sorts produce fining upward sequences in sediment; it’s a good phrase to know.It’s about this time when I wish they’d hurry up with the implants that will allow me to download things directly into my brain. But I digress.

One of the things I wanted to show you was the power of this river. It can and has carried boulders. It’s dropped boulders off when it’s done with them, and now amuses itself flowing over them.

And if you’re like me, you could sit on a boulder and watch the river play for absolute hours.No still photograph can capture the power of it. So I shot some video. First, we’ll pan up and down the river:

That gives you a general overview and some sense of how fast those waters flow. And in this one, I give you a close-up of some particularly interesting rapids. Pay especial attention to the fact there’s a person talking for a bit there. That’s my intrepid companion, and you can’t hear a word he says. Neither could I. The river drowned out everything except for itself.

And even that doesn’t really capture the magnitude of it. The deep roar of rushing water is something you feel as much as hear. It’s on the same order as standing right beside a freight train.

Right. So here we are, further up the river, and we can turn to look downstream back the way we came. Hard to believe we navigated all of those boulders:

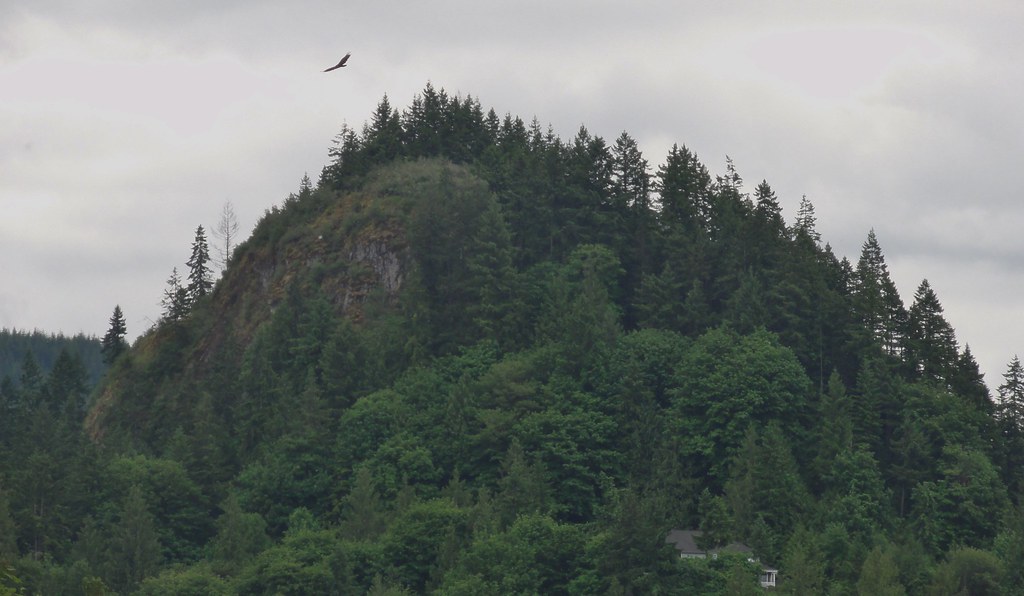

Not easy walking, I can assure you. I’ve heard of gravel bars, and cobbles, but I think this has to be dubbed a “boulder bar.”Looking upstream, we now have a better view of the mountains:

Okay, well, aside from the clouds trying to eat them, but this is the Pacific Northwest, people. We’re lucky we can see the mountains at all.If you look closely at the center-left of the bank, you’ll notice a gap in the trees, and a house that’s about to have a whole new definition of riverfront property. It might have had a back yard once, but the river ate it.

The clouds weren’t feeling particularly cooperative, but I did get a couple of close-up shots of the mountains. Here’s one where you can see just how precarious slopes can be:

If we’d got deeper into the Cascades, you would have seen quite a lot more snow, and possibly some glaciers, but this will do. Cliffs and crags with a bit of sunlight on are nice.In our next segment, I’ll be introducing you to some of the rocks that didn’t come home with me, and you will see some lovely examples of what being stuffed into a subduction zone can do to stone.