I spent four years on top of a type section, and I never knew it.

|

| Moi avec Page Sandstone, many years ago |

I lived on Manson Mesa, in Page, AZ, where the type section for the Page Sandstone is located (pdf). I knew it was sandstone. I thought it had been laid down in a sandy sea during the dinosaur years, and there my geologic awareness ceased.

My geological knowledge back then suffered from, let’s be generous and call them deficiencies. I wish I’d known then what I know now, because then I would’ve taken about ten trillion photographs of the place and gotten a lot more out of living there. Still. That landscape did settle into my soul. Slickrock country settled into my soul.

It’s stark, sand-scoured, barren but beautiful. I’d walk up the road from our house and along a dirt track, topping a rise on the mesa, and then partially descend the other side. That’s when it would hit: the most profound silence I’d ever heard. I’d stand there looking out over Lake Powell and just soak in the silence. It couldn’t have been all that much quieter back in the Jurassic, when the Page Sandstone was nothing but coastal dunes marching along for miles. They rested atop even older dunes, which are now the Navajo Sandstone. Sandy then and sandy now. You go to Page, you’ll become intimately acquainted with sand, both lithified and windblown.

Stand here, with me, on the sandy side of the hill. Look over the lake. Do you see that arm of the Colorado, meandering through the side canyons it’s carved into the ancient dunes?

|

| The Colorado River, or at least parts thereof |

You can play games with it, here, shift your perspective and spell things out. Just there, from that vantage, it’s a J. Move a few yards, and it’s a T. Walking back in time. Jurassic-Triassic. There may even be some Triassic rocks around here – I’ll find out next time I go, now that I know more, now that I can love it for what it was and not just what it is.

Back then, I’d just stand and stare at the sapphire-blue lake incongruous in the pale red desert, and wonder how the fuck anyone could possibly call a rock surrounded by nothing but rock “Lone Rock.”

|

| View of Lake Powell from Manson Mesa. Lone Rock is that rock in the middle ground on the right. |

On the other side of Manson Mesa, the wind has swept the stone clean, and you understand why it’s called slickrock. It’s smooth, almost slippery, although the grains of windblown sand locked in their matrix do a pretty good job providing traction, if you know how to work it. And I worked it. In slick-soled boots, on dunes turned rock that weathered into rounded tops and tiny ledges on steep slopes before becoming sheer drops. I’d run, flat-out, on ledges no more than a few inches wide, with nothing more than a few hundred feet of air on one side and high, rounded stone on the other, and I never once feared I’d fall. The slickrock wasn’t so slick for me. It gripped me, assured me it wouldn’t let me go. I could trust it implicitly, even the crumbly bits where erosion was returning the stone to its original sand. We understood each other, this sandstone and me. We knew each others’ limits.

There was a place on the edge of the mesa where flash-floods had carved a gully between rock walls, and those stood high above the desert floor like castle turrets. They were my citadel. When I was up there, I was queen in my castle. I could stand at the top of a turret and gaze over my treeless domain.

And it was treeless. Sagebrush, a few straggling junipers, and some unidentified bushes growing along the washes were about the limit. This is a stark, startling place, to someone who’d left an alpine paradise behind. No mountains, no ponderosa pines reaching for the sky. Just rock and sand with a desperate bit of biology barely clinging on, far as the eye could seen.

There used to be trees up there, legend says. This is a landscape for legends. You can believe nearly any wild tale you’re told, up there. You can believe the trailer park built to house the folks building Glen Canyon Dam exploded at midnight on Halloween night in 1959. You can believe skinwalkers stalk the darkness. Just listen to the way the coyotes’ howls echo off those stone walls, refract and reflect and become something supernatural. You know where those legends arise, now. You know why, when people tell this story, you can believe it:

Back in the 1800s, a cowboy was passing near Manson Mesa on his way to Lee’s Ferry with a Navajo guide. No lake there, then, and precious few ways to cross the Colorado, which had been cutting its way down into the Plateau for millions of years. But there was this mesa, and the cowboy wanted to go up there and have a look. The Navajo guiding him refused to take him up. The cowboy demanded, the Navajo steadfastly refused. The cowboy finally demanded to know why.

“The top of that mesa used to be covered with trees,” the guide said. “There used to be a forest. But something evil came to the mesa. It scared the trees to death.”

The cowboy scoffed, went up alone, and never came back down.

Something so evil it scares trees to death. Yes, sometimes, that’s what you feel up there. But only close to the city. On the side of the mesa, where it’s still wild, you may keep a weather eye out for skinwalkers, and you may feel like a very tiny thing lost in the vastness of the desert, but lean back against the slickrock and absorb the silence and you’re suddenly more at peace than you ever thought you could be.

Besides, if you’re a geologist, you’d probably like to find that evil thing and thank it profusely for getting rid of all that pesky biology in the way of the rocks.

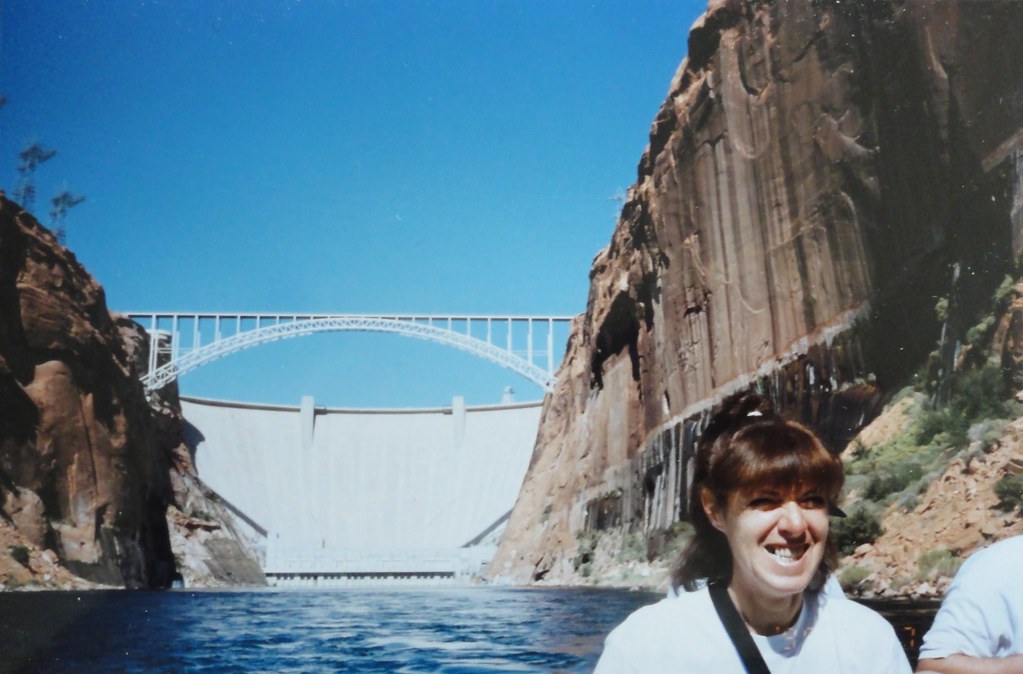

There’s another place, and another way, to see the rocks round there. Down by Glen Canyon Dam, you can hop in a raft and run the river. I never did, but my mother did, and thanks to her, we have some views that only a few people ever see.

|

| My mother, with Glen Canyon and Glen Canyon Dam as her backdrop |

I believe that canyon is cut from the older, far more extensive Navajo Sandstone, but you’d be doing me an unkindness by holding me to it.

Still. Go up on the bridge over the dam. There’s a walkway for pedestrians, and you can look down down down into a chasm where the Colorado flows, through sandstone walls painted dark with desert varnish. You’ll get deliciously dizzy, standing there with a vertical drop and vertical walls. If you’re very lucky, you’ll be there on one of those days when clouds are scudding across the sky, and you can watch sun and shadows play spectacularly artistic games on the ancient stone. You can watch them release water from Lake Powell, keeping the Colorado flowing and the power generating, and see how wild the river can be.

|

| The Colorado roaring down Glen Canyon |

There are some places you have to leave to love. For me, Page is that place. All I ever wanted or needed while I lived there was to get the hell away. Now, I’m older and wiser and miss it quite a lot. My beautiful, barren, bewildering slickrock country, I’ll come home soon. Just for a while.

And I’ll come away with a piece of you, just so I can waggle it at visitors and say, “Ha! Look at this, bitches – a piece of the type section of the Page Sandstone!” Because there are few things in this world that a geology buff could love doing more.